at Our Friendly Neighbours, Korean Cultural Centre, London, UK, 8 SEP - 5 NOV, 2022

at Hacking the Gravity, Commde Design Centre, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand, 29 OCT - 18 NOV, 2022

at Hacking the Gravity, Commde Design Centre, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand, 29 OCT - 18 NOV, 2022

at MMCA Cheongju Rooftop Project 2024, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, Cheongju, Korea, 13 SEP - 31 DEC, 2024

at BY ART MATTERS, Hangzhou, China, 22 April 2025 - 22 April 2026

Wandering Sun, 2024.

Single channel video installation, Unreal Engine 5, AI algorithm, NASA Earth observation data, 4 x 17m 2.6pt, 04'15"

Highly advanced AI technology is creating incredibly realistic images that are consumed through various multimedia environments. I wonder which sunrise remains the most beautiful in the hearts of those who have seen it in real life, in movies, or experienced it in a game. Korean landscape painting has a different context from Western landscape painting. It's based on a different worldview. Understanding landscapes depends on how we perceive nature, the universe, and technology. In "Wandering Sun," the sunrise over the sea actually emerges from the floor of the exhibition space. The entire space turns red due to light reflection, transforming the natural sunrise phenomenon into a spatial transformation within the exhibition hall. This aims to deliver a synesthetic and holistic experience of sound and light.

Above all, I wanted to talk about the epistemological crisis caused by AI. We are entering an era where science and technology artificially control our senses more precisely. We may be trapped in our own senses, including sight. We must stay awake. The sun rising from the floor moves slowly clockwise, following the frame of the previous video. Despite being an impossible phenomenon in real landscapes, it looks very realistic. This is because phenomena like changing clouds and light reflection are simulated so realistically by advanced AI technology. Are we living in a 'Truman Show' that has been created? "The Truman Show," released in 1998, is about a TV show that broadcasts the entire life of a man who doesn't know he's living in a studio designed to look like reality to the whole world. We were the viewers observing the protagonist in the movie, but now, is AI in a position to observe us? AI is like a giant mirror. It collects my information and shows me based on that data. However, the way the real world sees me may be different. But AI eliminates this difference and shows only the image of myself that I want to see. It may feel good, but it detaches from the complexity and authenticity of the real world, makes everyone dependent on their own fantasy world, and ultimately distorts our understanding of the world, putting us at risk of further disconnecting communication with others. Through this virtual sunrise video that slowly flows clockwise along the frame of the video, I wanted to poetically show the wandering crisis of humanity.

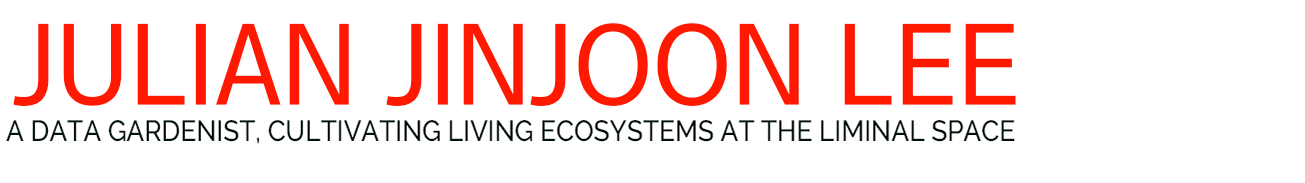

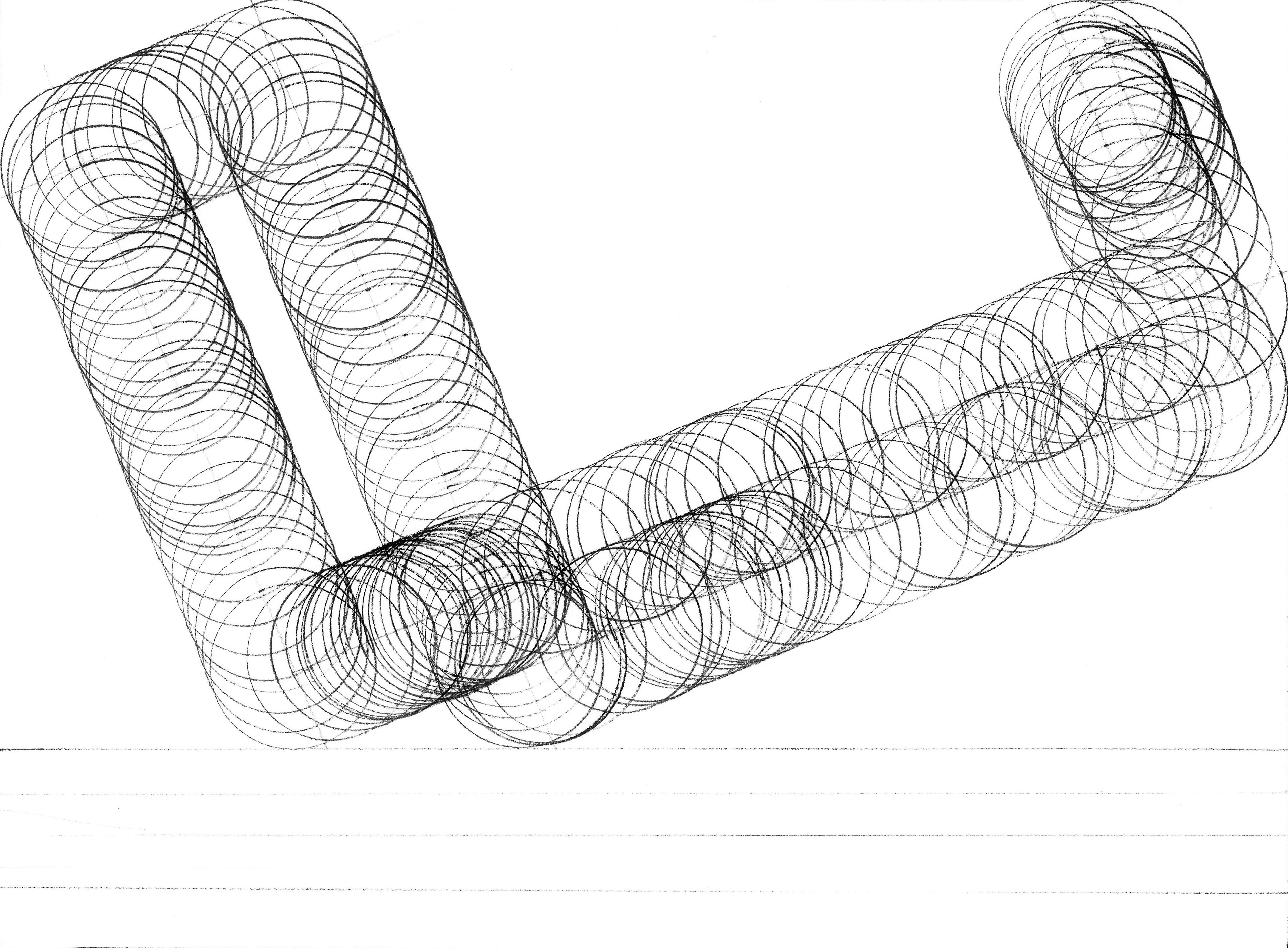

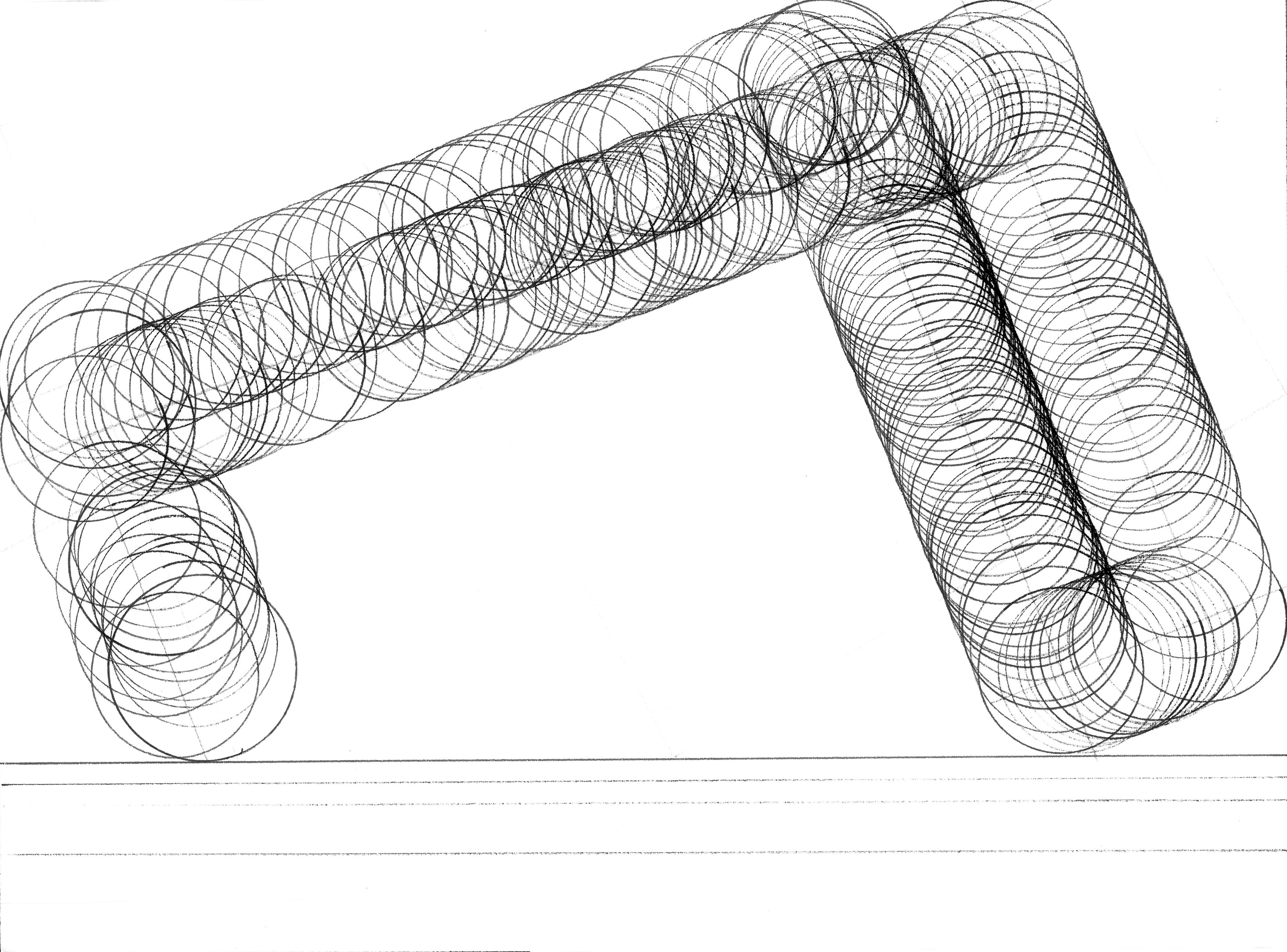

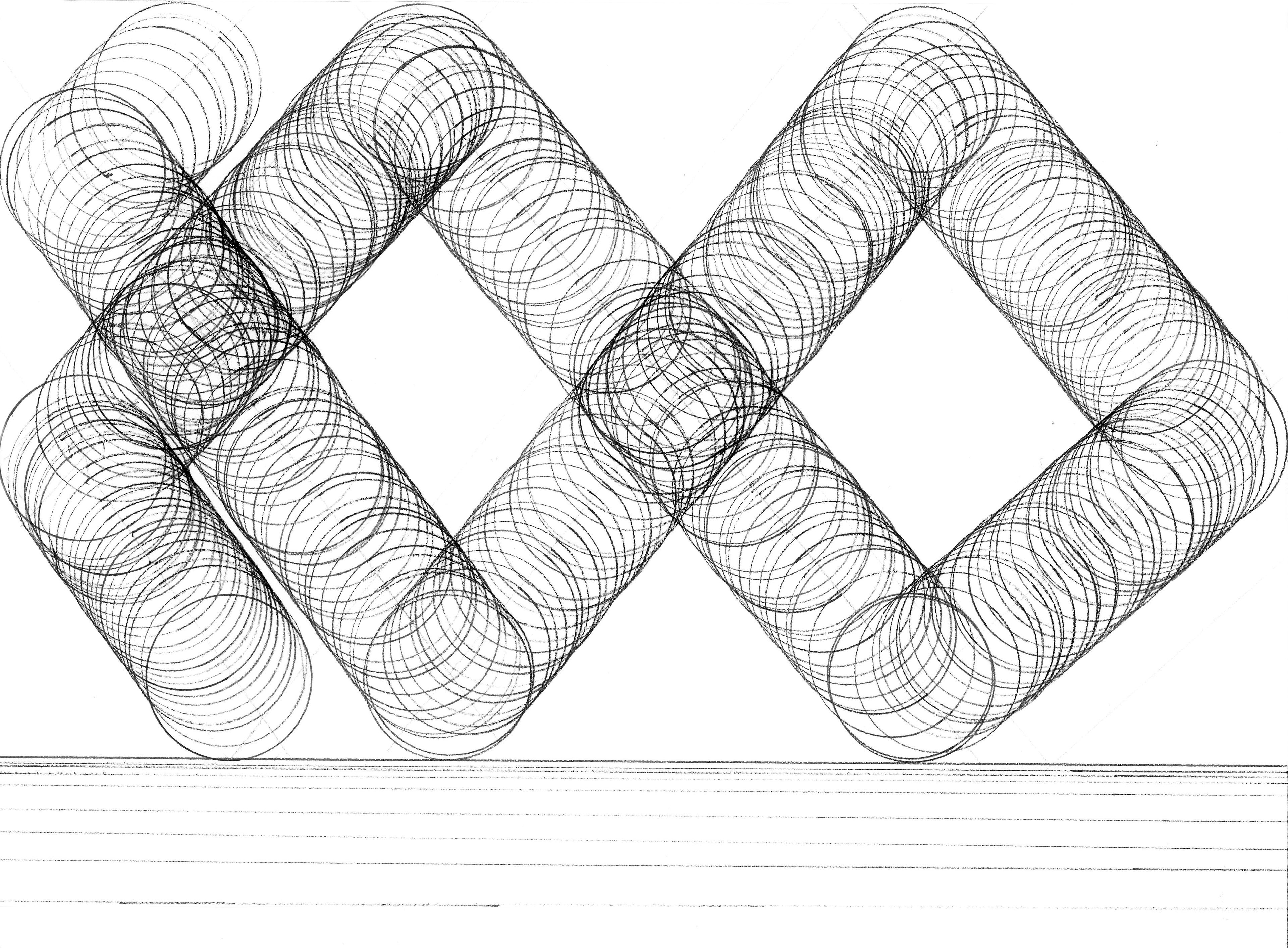

Julian Jinjoon Lee, 〈Wandering Sun〉, 2024. drawing with pen, 23 x 31cm.

Artist Note

The Wandering Sun in Liminality

“Daybreak is a prelude, and nightfall an overture—an overture which comes

at the end, and not, as in most operas, at the beginning.” [1]

– Claude Lévi-Strauss, Tristes Tropiques (1955)

at the end, and not, as in most operas, at the beginning.” [1]

– Claude Lévi-Strauss, Tristes Tropiques (1955)

Lévi-Strauss’s metaphor of sunset as an operatic overture poignantly captures the symbolic interplay between nature and humankind. This imagery reflects his profound insights into the relationship between the natural and the cultural. By systematising the human experience of sunset as a cultural phenomenon, Lévi-Strauss investigated the ways in which we connect ourselves to the world.

I vividly recall my first encounter with this text at the age of twenty. Immersed in Lévi-Strauss’s intellectual odyssey and his far-reaching reflections on humanity and society, I was struck with awe: how could a single human mind attain such heights of thought? Accompanying him on his journey through South America, I devoured each page with a blend of boundless curiosity and the bittersweet awareness that the book’s journey would inevitably end. As I continued reading, I often felt a subtle pang of regret upon observing the steadily dwindling number of remaining pages. Looking back, my own wandering—leaving my hometown, the small city of Masan and travelling across more than sixty countries over the past thirty years—truly began in that moment.

What most captivated me was Lévi-Strauss’s ability to balance the rigour of reason with an abiding affection for humanity. He critiqued the Enlightenment’s tendency to elevate science and technology at the expense of myth and sensibility.[2] For him, myth was a vital tool, harmonising emotion and reason within a coherent framework of human understanding.

Ra and Imentet from the Tomb of Nefertari, 13th century BC

The sun has always occupied a central place in humankind’s myths. Its rising and setting are not mere celestial occurrences, but the very rhythms of life itself. Across diverse cultures, the sun has served as a potent metaphor: in East Asian yin–yang philosophy, it represents yang—symbolising brightness, intensity, activity, masculinity, and warmth.[3] In Confucianism, as exemplified by the Ilwolobongdo (Sun, Moon, and Five Peaks), it signifies royal authority.[4] In ancient Egypt, the sun god Ra embodied creation, life, and resurrection.[5] Thus, the sun and its cycles have long symbolised life and death, beginnings and endings.

However, in a modern, technology-dominated society, even the sun is losing its mythic resonance, reduced to little more than a data point and understood solely as a physical phenomenon. By capturing the moment of this symbolic loss within a technological framework, I aim to pose questions regarding the sun’s inherent meaning and to reconsider the depth of the symbolic and sensory connections it forges between nature and human experience.

[3] Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 2, Cambridge University Press, 1956.

[4] Cultural Heritage Administration of Korea. (2024). Ilwolobongdo (일월오봉도): Sun, Moon, and Five Peaks. Retrieved December 23, 2024, from https://www.heritage.go.kr/

[5] Pinch, Geraldine. Egyptian mythology: A guide to the gods, goddesses, and traditions of ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, USA, 2004.

<Ilwol Obongdo (日月五峯圖)>

Six-Panel Folding Screen, Artist Unknown, 19th Century, Color on Silk, 151.4 × 94 cm. National Palace Museum of Korea.

Six-Panel Folding Screen, Artist Unknown, 19th Century, Color on Silk, 151.4 × 94 cm. National Palace Museum of Korea.

The Wandering Sun finds its origins in this context. The project exhibited at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Cheongju is based on thirty years of climate data, gathered since I left my hometown of Masan. Drawing on information from NASA and various meteorological agencies, in conjunction with Unreal Engine and AI algorithms, these datasets were transformed into dynamic visual sequences. From this synthesis emerges an interplay of clouds, waves, and the sun, displayed on a vast LED screen in which the sun rises and sets according to a digital rhythm rather than the cadence of nature. Standing before this monumental installation, viewers might well find themselves asking whether this sun is ‘real’ or ‘virtual’.

Yet the true essence of the work lies not in the sun’s visual realism, but in the ways in which the audience traverses the boundaries of perception. Much like taking photographs against the backdrop of a digital sunset, viewers engage with the sun as both spectacle and experience.

The project began with an analysis of NASA’s MERRA-2 data (Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2), tracking fluctuations in SO₂ concentrations. My team at KAIST’s TX Creative Media Lab focused on thirty years of climate data from Masan, extracting time-series datasets using Python and formatting them into CSV files. Further meteorological data from the Korea Meteorological Administration—encompassing temperature, humidity, wind, and pressure—produced six comprehensive datasets.

These datasets were then imported into Unreal Engine and converted into data tables, before being integrated into the project’s timeline. Variables such as the Rayleigh scattering scale were dynamically adjusted over time, allowing the sun’s motion, the sky’s gradual colour transitions, and the refraction of light to evolve in real time. By harnessing Unreal Engine’s sequencer and data-streaming capabilities, we constructed a landscape that feels both hyperreal and vividly animated.

<Climate Data and Game Engine Application in Wandering Sun>

This process is not confined to a straightforward exercise in data visualisation. Rather, transforming climate data into a digital landscape demands not only precision in technique but also generates an aesthetic encounter, encouraging viewers to contemplate the relationship between the sun, nature, and humanity. My aim was to illuminate the connection between humankind and the natural world, and to highlight the tension between the artificial rhythms shaped by technology and nature’s intrinsic pulse. Far from being a simple instance of data visualisation, it harbours the potential for what Rosalind E. Krauss calls a ‘post-medium’. [6] By evoking a sense of mythic nostalgia—tied to distant origins—and accentuating the algorithmic recursion inherent in game-engine imagery, the piece amplifies this effect through its vast LED screen set into the floor.

Rising and setting on the museum floor, staining and reflecting its surroundings, this sun is not simply a heavenly body travelling across the sky. It becomes an inquiry into the world we inhabit and our manner of engaging with it—an inquiry taking place in the present moment. In this respect, the space operates as a programmed stage, placing the audience within a transient, liminal space.[7]

In this sense, I intended to explore the relationship between technologically created landscapes and the human presence within them, akin to the manner in which traditional East Asian landscape paintings contemplate humanity’s place in nature. Whilst technology offers a level of realism once thought impossible, it simultaneously supplants the reality we might otherwise encounter, rendering its essence obscure. Rather than experiencing nature directly, contemporary individuals consume its representation as spectacle through screens and digital devices. Consequently, the sun on screen has, for many people, become the only sun they truly witness. We have entered an era in which it is scarcely possible to distinguish between what is fabricated and what is genuine. Yet that sun is no longer absolute; it is manipulated by technology, constrained within a restrictive frame, floating indifferently in an endless loop. The Wandering Sun confronts viewers with this paradox, so that the sun, rising and setting within its frame, ceases to be merely another moving image, instead serving as a metaphor for the anxiety and disorientation of modern individuals who have lost any firm sense of direction.

Insomnia, 2006. Single channel video and sound installation, 03'40"

These concerns are closely intertwined with my earlier works. In Insomnia (2006), I investigated the surreal tensions present in liminal spaces, while from 2008 onwards, the Your Stage series—also referred to as Black Moon—invited the audience to become part of the performance, immersing themselves in the work’s interplay of light and space, thereby entering a liminoid experience.[8] In this new piece, too, viewers are far from passive observers; they respond to the sun’s movements and, however subtly, are prompted to question where they stand amid light and shadow. By placing them in this disconcerting yet undeniably compelling aesthetic, I hope—even if only momentarily—that they might confront the often unfamiliar depths of their relationships with self and world, as well as with technology, nature, history, and myth.

[8] Turner, Victor. From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play. PAJ Publications, 1982.

Your Stage, 2008. Light installation with LED, glasses, stainless steel, variable size.

Contemporary AI technologies are generating strikingly realistic images, then consumed across myriad multimedia environments—a phenomenon further driven by the rise of generative AI. Amongst those who have witnessed a sunset directly, or through film, gaming, or on social media platforms such as Instagram, one might well ask: which sunrise or sunset remains most vivid in our shared memory?

We are entering an era in which the belief that science and technology merely broaden our senses is overshadowed by a disquieting truth: these systems increasingly manipulate and regulate our

senses with precision. The overconsumption of images has prompted a perceptual imbalance, selectively unsettling our sensory experiences. Phenomena that could never transpire in the natural world now appear startlingly real, forcing us to confront the constructed nature of our technologically mediated surroundings. It is as if we ourselves were participants in a fabricated Truman Show.[9]

The 1998 film The Truman Show depicted a man who, unbeknownst to him, lived his entire life within a meticulously crafted simulacrum of reality, aired worldwide as a form of entertainment. If audiences once watched Truman as detached onlookers, in our present day it appears we have become the observed, monitored and analysed by artificial intelligence. AI functions as a gargantuan, Earth-sized mirror, collecting our data and reflecting selectively curated visions of ourselves back to us. This recursive feedback loop alienates us from the complexity and genuineness of reality, confining us to increasingly individualised and fractured worlds.

At the heart of this distortion lies an epistemological crisis, arising from our inability to tell truth from fabrication. The irony of Truman’s friend marvelling at an entirely constructed sunset—praising its perfection as though it were natural—mirrors the key question of The Wandering Sun. Even as it presents scientifically impossible scenes, the work elicits aesthetic and emotional resonance, confronting us with our own complicity in a world where artificiality is consumed as beauty. Mundus vult decipi, ergo decipiatur (“The world wants to be deceived, so let it be deceived”). People hear only what they wish to hear and see only what they wish to see, believing only what they choose to believe. In this so-called era of generative AI, the world may well be awaiting its own deception. In the face of such a precarious technological landscape, we as artists must ask ourselves: what are we to hope for?

[9] Weir, Peter, director. The Truman Show. Paramount Pictures, 1998. Film.

In The Truman Show (1998), there's a scene where the main character's friend describes how perfect and beautiful the sunset is. However, scientifically, the moon and the sun could never actually align that way.[10]

The boundaries between art and academia are dissolving, giving rise to an era in which creation and research mutually enrich one another. Contemporary artists probe beyond purely aesthetic expression, venturing into social, scientific, and philosophical considerations, while scholars adopt innovative, creative modes of problem-solving that borrow from the artistic realm. This convergence heralds the emergence of the artist-scholar, a figure uniquely placed to navigate the decisive intersections of these disciplines.

With the growth of digital technologies, data analysis, AI, and XR, artists are increasingly compelled to reconcile critical inquiry with creative practice. The Wandering Sun embodies this balance, moving beyond Western traditions of representational landscape art. Instead, it incorporates the audience’s body and sensory perception into the work, erasing distinctions between human and non-human. Such an approach resonates with the notion of mindscape (心象) in the East Asian landscape painting(山水畵sanshui), wherein the external environment is not merely observed but fully absorbed, dissolving the boundaries between subjective and objective realms to reveal their profound interplay.

Through the symbolic processes of coding and decoding scientific data, historical facts, subjective introspection, and multi-sensory mythologies, The Wandering Sun explores how these layers might coexist within a digital framework. By tracing the semantic imprints left by visual and sensory interactions, the work investigates the intricate interplay between nature, humanity, and technology. This enquiry aligns with my broader exploration of brain-computer interaction in art—commonly known as Brain Art—where human brain signals inspire new creative possibilities. By employing such innovative tools, I seek to uncover dimensions of meaning that transcend traditional boundaries. The work represents both an act of discording—deliberately unsettling familiar dichotomies—and a considered attempt to transcend binary thinking. It aspires to dissolve the separations between subjectivity and objectivity, nature and the artificial, striving instead to integrate and harmonise these realms into a unified and cohesive understanding.

[10] In The Truman Show, Marlon tells Truman: "Look at that sunset, Truman. It's perfect. ... That's the big guy. Quite a paintbrush he's got." (The Truman Show, directed by Peter Weir, Paramount Pictures, 1998)

In The Wandering Sun, the sun flows and roams, endlessly repeating its cycle yet remaining confined to its frame. This wandering sun mirrors the existential predicament of modern humanity, locked into the ceaseless repetition of technologically mediated existence. The hyperreal images generated by AI and digital technologies blur the boundaries between real and virtual, depriving us of any definitive notion of truth. As we forfeit nature’s rhythmic pulse, we fall subject to the rapid tempos imposed by technology.

Paul Virilio cautioned that speed and technology warp our perceptions of time, eroding the very foundations of meaning.[11] Rising from the museum floor to envelop the surrounding space, The Wandering Sun encapsulates these distortions, embodying the tension between natural and artificial tempos. No longer adhering to the leisurely pace of a natural sunrise and sunset, this sun follows the strictures of technological systems, awakening nostalgia for nature’s lost mythic symbolism.

Yet The Wandering Sun does more than lament this absence. Though confined within its frame, it ceaselessly re-explores itself, engaging in a recursive dialogue with its environment. Over the course of its four-month run—attuned to day and night, autumn and winter—The Wandering Sun repeatedly transforms its surroundings. Though it remains bounded, it holds open the possibility of surpassing its own confines. Here, too, the audience might reflect on themselves in this liminal context. Even within the constraints of the screen and beyond the spectacle of the digital sphere[12], human beings retain the capacity for rediscovery. My hope is that, in posing the question of where we might find hope amid the disquiet of the digital age, this installation once again provides visitors with the chance to reckon with both the barriers and the possibilities set before them.

Often, we do not fully apprehend what we are really viewing. Even the spectacle of dawn and dusk, once so immediate, is now replaced by technologically crafted images. Within The Wandering Sun, the interplay of light, reflection, and refraction surpasses the boundaries of pure aesthetic representation, serving instead as a reminder of what may yet be unveiled at the frontiers of perception. Even in the digital age, human beings retain the ability to pose the kind of probing questions that venture beyond the immediate, towards the deeper and the enduring. What, then, is genuine? Where do we stand? And what are we heading for?

Artist Julian Jinjoon Lee

Art Director Sun Kim

Technician Sungback Kim

Producer Doyo Choi

Support

Korean Cultural Centre UK (KCCUK)

Art Center Nabi

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea