On Some Faraway Shore No.2, No.6, No.4, 2025. Photography by BB&M Gallery.

Artist Note

Nine Reincarnations

Reconfiguring Memory in the Post-AI Era

* In January 2026, this essay was featured in the special issue “The Cutting Edge of Contemporary Korean Art”(「韓国の現代アート最前線」) of the leading Japanese art journal Bijutsu Techo (美術手帖). The magazine invited him to contribute an essay titled “Nine Reincarnations: Reconfiguring Memory in the Post-AI Era” (九度の転生──ポストAI時代における記憶の再構成), in which he reflects on his Nine Reincarnations project and explores how memory, image and affect are transformed in a post-AI landscape.

I am ‘placed’ [1]

Logged in through my iris, I find myself in a vast, nameless ‘Theatre of Memory’[2]. It sinks like a black lake. From the ceiling, another gaze holds me. Layers of memory, countless images, turn slowly and monumentally. The gaze is not mine. It is theirs. When one scene slips into the next, it ceases to be an it and opens as landscape.[3] Here, on this theatre where what I look at looks back, I am placed.

I try to unspool a filament of mind and fix it on a single point, yet it keeps missing and keeps slipping. A light vertigo recalls the surge of release that rose when the wind off my home sea touched my cheek long ago. In those days I chased the sunlight skimming the horizon and stopped before a rusted iron bridge. The water stilled beneath my feet, summer with soapy brine and winter with an enamel chill. Smoke shouldering up from the chimneys across the pier summons the “freedom” of the Free Trade Zone[4] with a delicate olfactory memory. Can a machine remember even that scent, a mix of salt and enamel? This finite disk, near-infinite, waits to be called up before our eyes as images of resolution higher than the real. In the excess, my frail memories evaporate at the very moment they form. Yet that very strain has become the art of summoning memory.

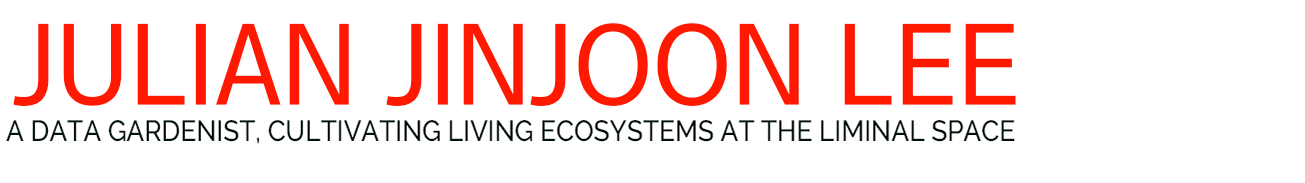

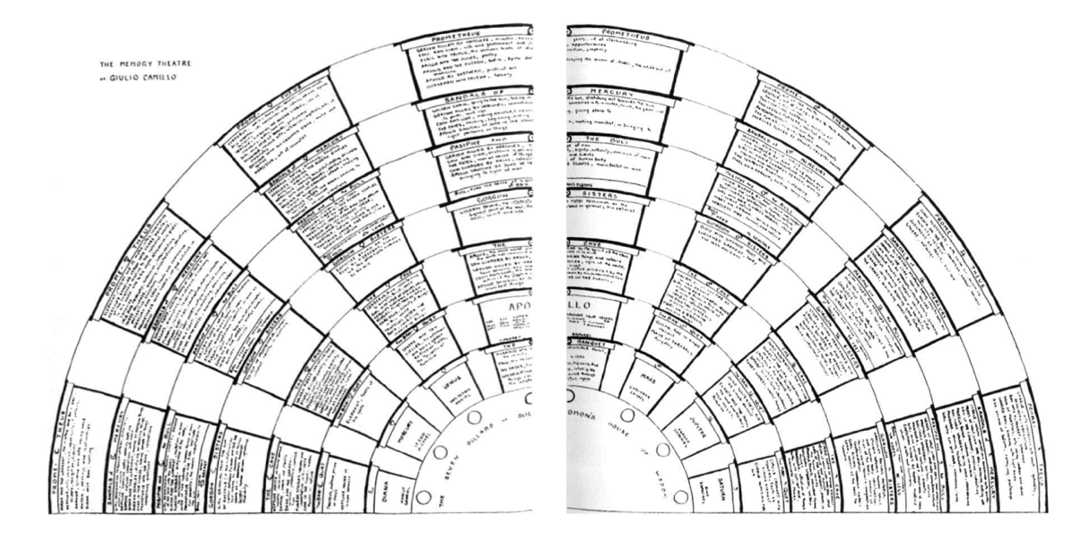

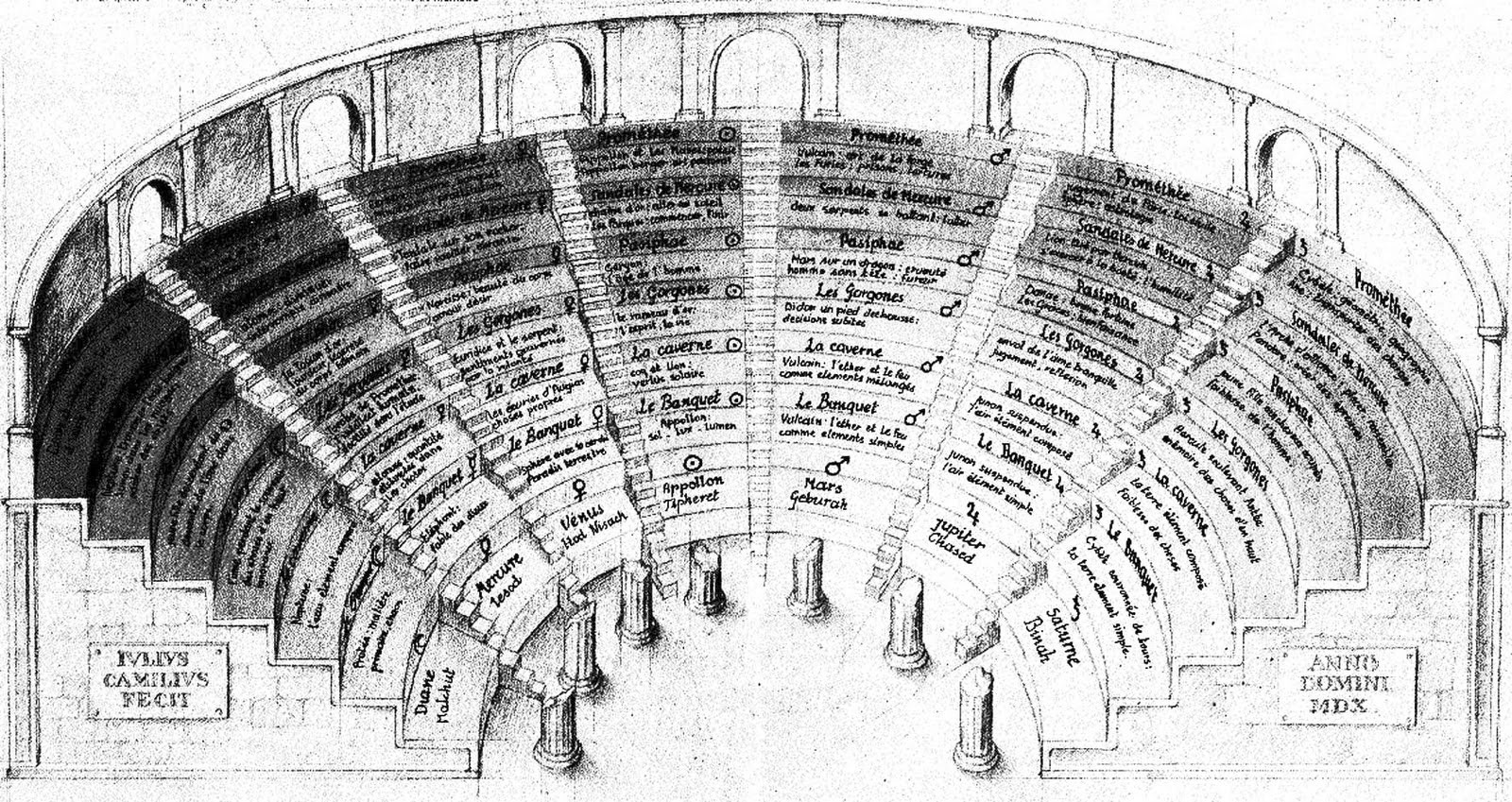

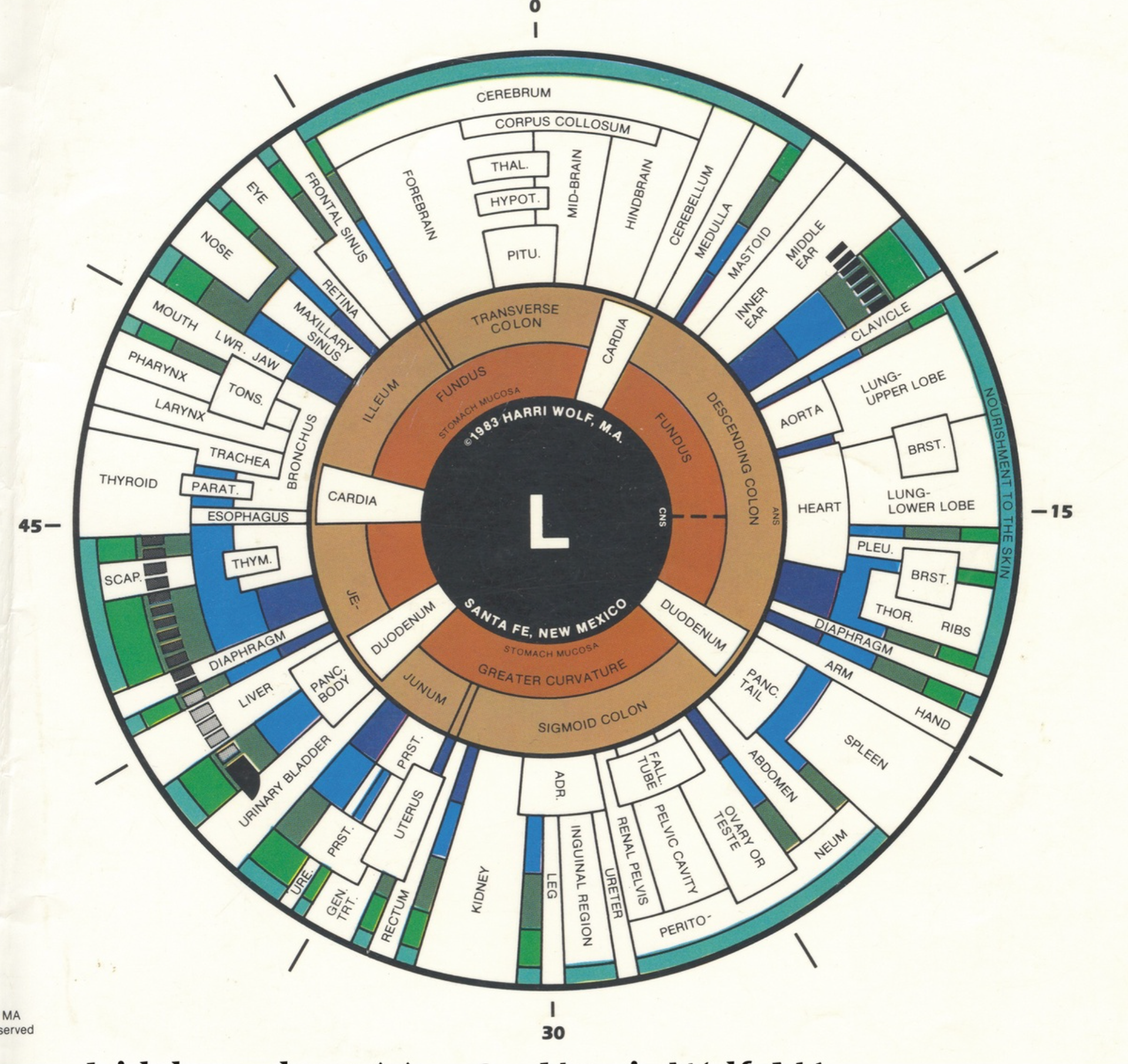

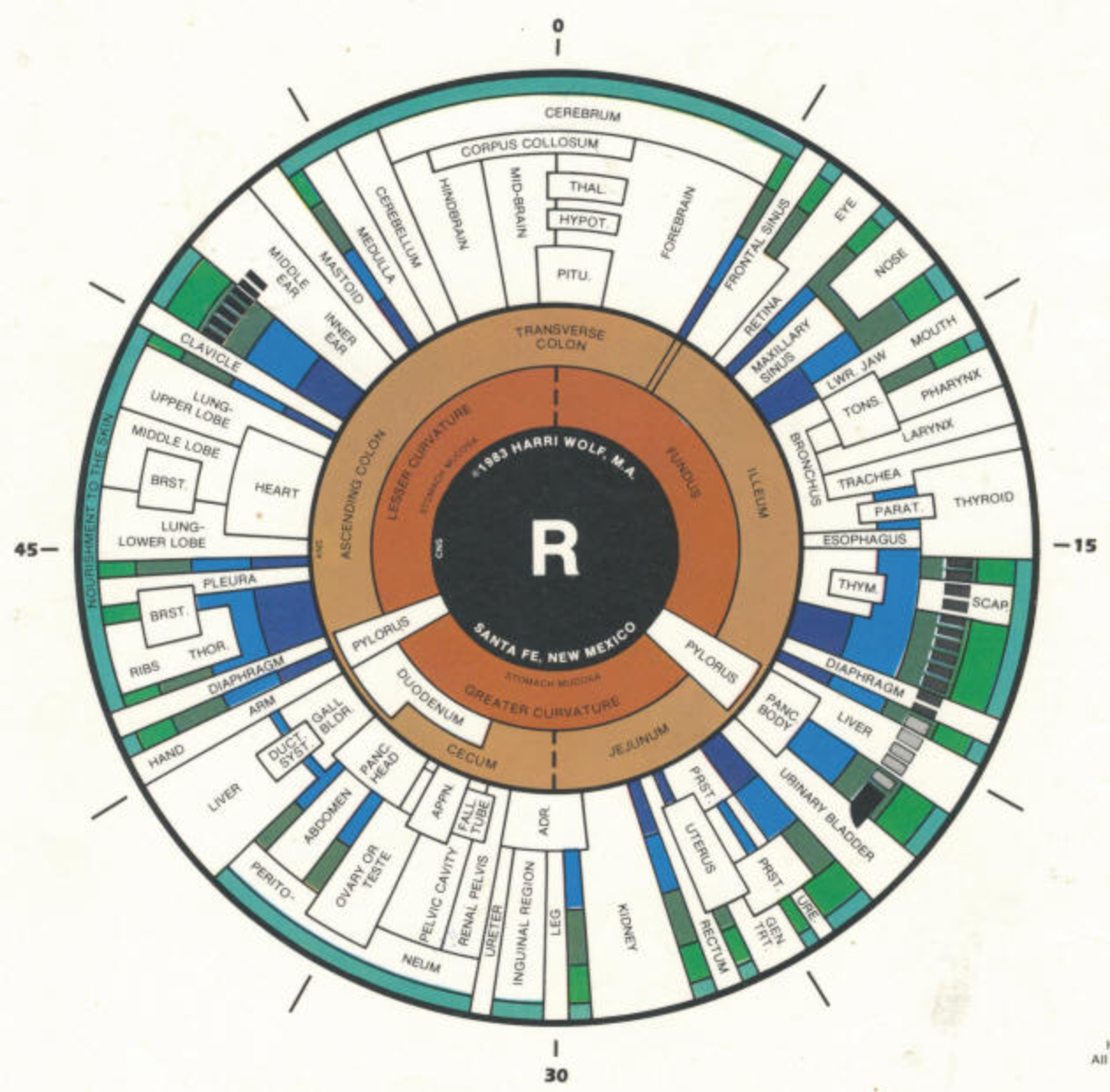

In the fifth century BCE, Simonides [5] identified the unrecognisable dead in a collapsed banqueting hall by recalling the order of places. Ancient orators borrowed buildings and streets, weak and provisional places, for a day, turning them into ‘a memory palace’[6] in which to rehearse speeches that changed daily. At last, the Renaissance philosopher Giulio Camillo[7] envisioned a circular theatre where memory opens at a glance and invited a solitary person to the stage. It was an ideal that would pin forever a truth unworn by time, the essence of all that can be said. This theatre of memory, bearing the symbolic order of an unchanging cosmos, was designed so that eternity’s truth could always be called forth.

On Some Faraway Shore No.3 & No.7, 2025. Photography by BB&M Gallery.

[1] The artist describes this state as the experience of submerging in a solitary, foreign void opened by the formation of boundaries. The audience of his work ‘Half Water, Half Fish’(2007), a performance art piece, found themselves in this state as island-like boundaries of personal space were formed by actors. (Julian Jinjoon Lee, Nowhere in Somewhere (Seoul: marmmo press, 2023), 26–33.) Brecht also touches on the topic of boundaries by talking about “the fourth wall,” a wall dividing the audience from the stage and thus forming the illusion that the action on stage is a form of reality. Bertolt Brecht, Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic, trans. John Willett (London: Eyre Methuen Ltd., 1974), 136. See also Jacques Rancière, The Emancipated Spectator (Le spectateur émancipé), trans. Gregory Elliott (London: Verso, 2011).

[2] The Theatre of Memory is a system of memory palace (see note 6) envisioned by Giulio Camillo (see note 7). The theatre is a semi-circular stage, rising in seven grades and divided by seven gangways, with an image-decorated gate on each divided area. A solitary ‘spectator’ looks outwards at the auditorium from where the stage should be, at the images on the seven times seven gates on the seven rising grades. Frances Amelia Yates, The Art of Memory (London: Ark Paperbacks, 1984), 129–159.

[3] Kōjin Karatani talks about the discovery of landscape as a process that occurs within the “inner man” at a state of indifference to external surroundings, landscape only perceived by those who do not look “outside.” Kōjin Karatani, Origins of modern Japanese literature (Nihon kindai bungaku no kigen), trans. Brett de Bary (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993), 25.

[4] Masan Free Trade Zone(MFTZ) is the first-ever foreign exclusive industrial complex in Korea, established in 1970 for the national and regional economy. “About MFTZ,” Masan Free Trade Zone Office, accessed August 13, 2025, http://www.motie.go.kr/kftz/en/masan/masanFTZ/aboutMFTZ.do.

[5] Greek lyric poet Simonides of Ceos, the inventor of the art of memory. Following a banquet hall roof collapse and the crushing of victims into unidentifable corpses, Simonides was able to indicate to relatives who was who by remembering the places at which everyone had been sitting. Frances Amelia Yates, The Art of Memory, 1–2.

[6] A memory palace, also known as the method of loci, is a mnemonic device where images placed in imagination on a sequence of places in a building are used to chronologically aid memory through imaginative moving through the memory building. Frances Amelia Yates, The Art of Memory, 3.

[7] Giulio Camillo Delminio, a Renaissance polymath, was one of the most famous men of the sixteenth century, known for his Theatre of Memory (see note 2). Frances Amelia Yates, The Art of Memory, 129–159.

[2] The Theatre of Memory is a system of memory palace (see note 6) envisioned by Giulio Camillo (see note 7). The theatre is a semi-circular stage, rising in seven grades and divided by seven gangways, with an image-decorated gate on each divided area. A solitary ‘spectator’ looks outwards at the auditorium from where the stage should be, at the images on the seven times seven gates on the seven rising grades. Frances Amelia Yates, The Art of Memory (London: Ark Paperbacks, 1984), 129–159.

[3] Kōjin Karatani talks about the discovery of landscape as a process that occurs within the “inner man” at a state of indifference to external surroundings, landscape only perceived by those who do not look “outside.” Kōjin Karatani, Origins of modern Japanese literature (Nihon kindai bungaku no kigen), trans. Brett de Bary (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993), 25.

[4] Masan Free Trade Zone(MFTZ) is the first-ever foreign exclusive industrial complex in Korea, established in 1970 for the national and regional economy. “About MFTZ,” Masan Free Trade Zone Office, accessed August 13, 2025, http://www.motie.go.kr/kftz/en/masan/masanFTZ/aboutMFTZ.do.

[5] Greek lyric poet Simonides of Ceos, the inventor of the art of memory. Following a banquet hall roof collapse and the crushing of victims into unidentifable corpses, Simonides was able to indicate to relatives who was who by remembering the places at which everyone had been sitting. Frances Amelia Yates, The Art of Memory, 1–2.

[6] A memory palace, also known as the method of loci, is a mnemonic device where images placed in imagination on a sequence of places in a building are used to chronologically aid memory through imaginative moving through the memory building. Frances Amelia Yates, The Art of Memory, 3.

[7] Giulio Camillo Delminio, a Renaissance polymath, was one of the most famous men of the sixteenth century, known for his Theatre of Memory (see note 2). Frances Amelia Yates, The Art of Memory, 129–159.

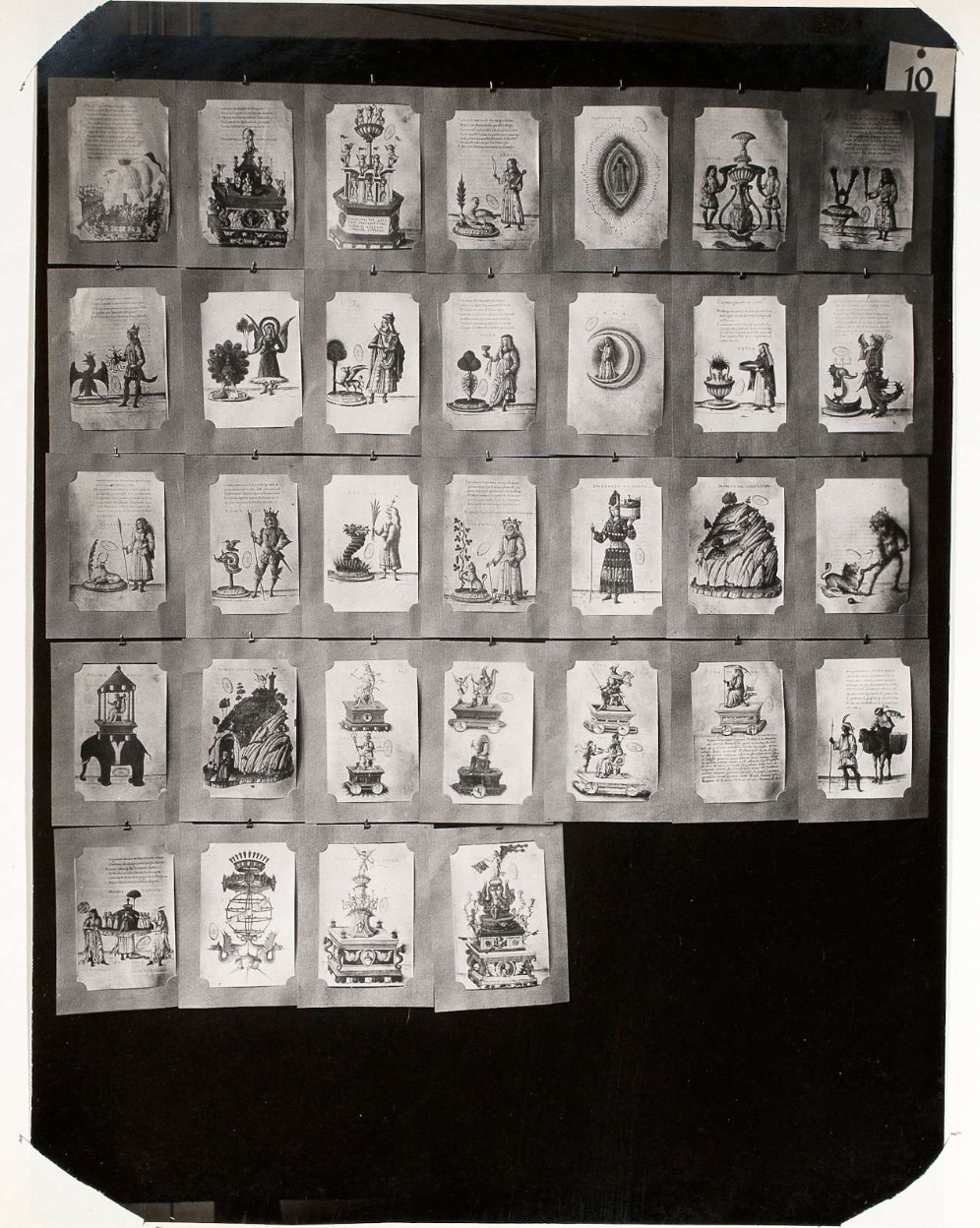

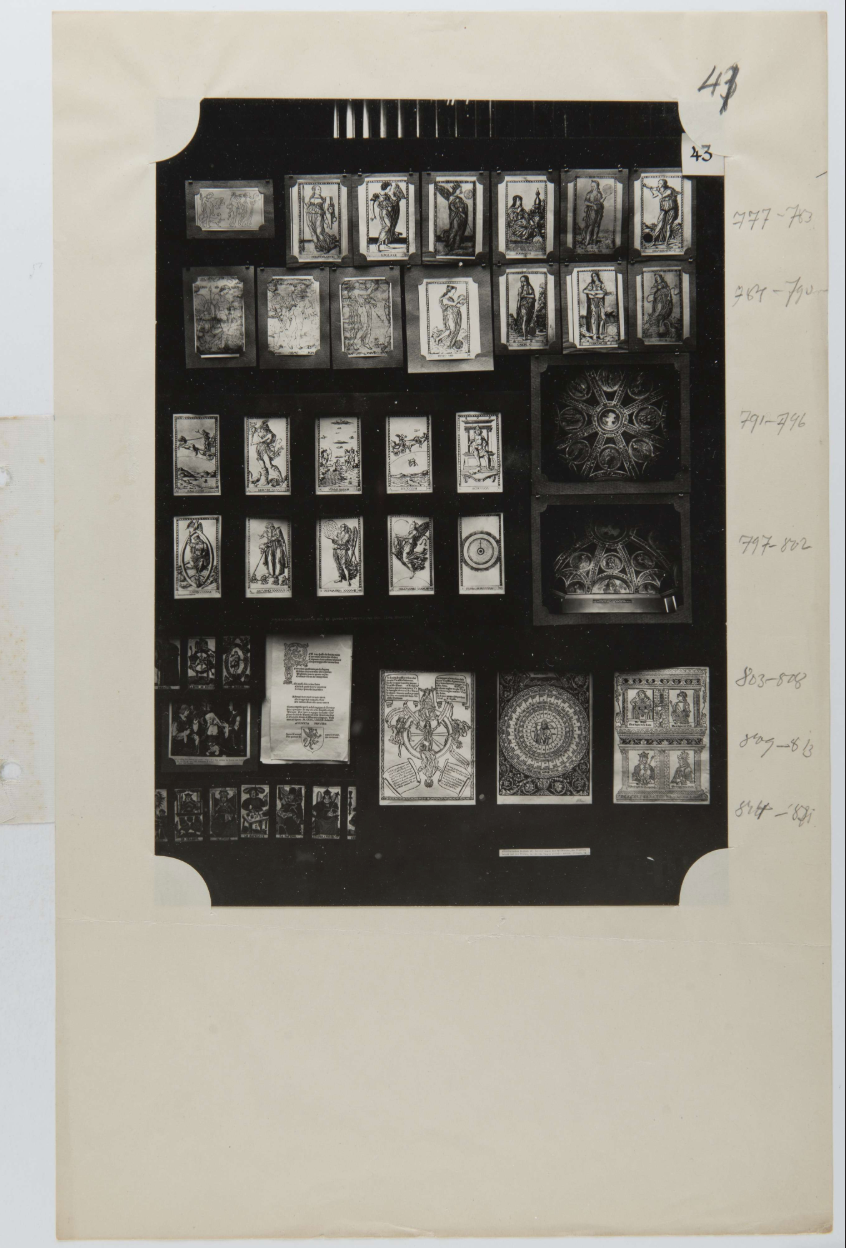

Fig. 1

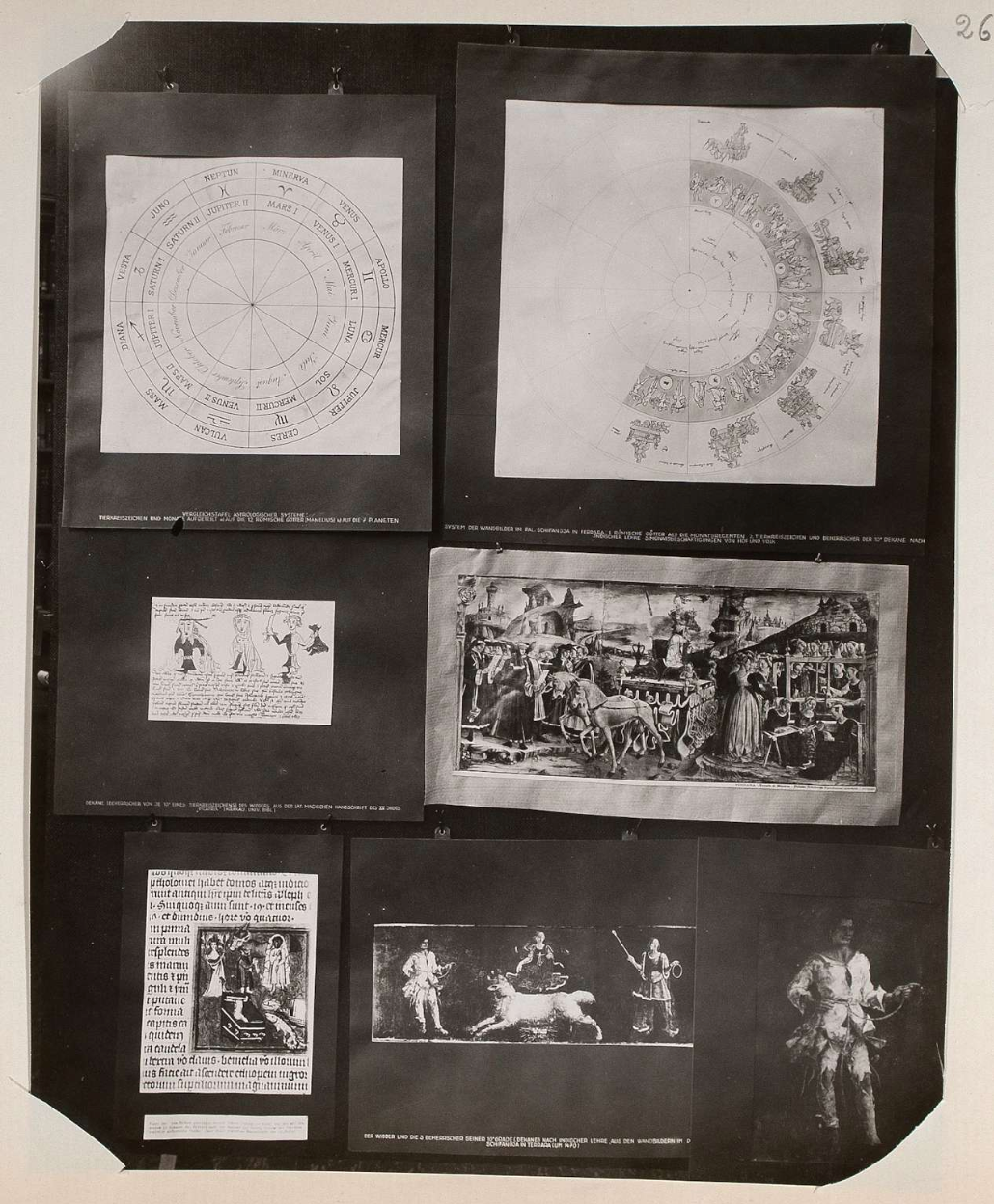

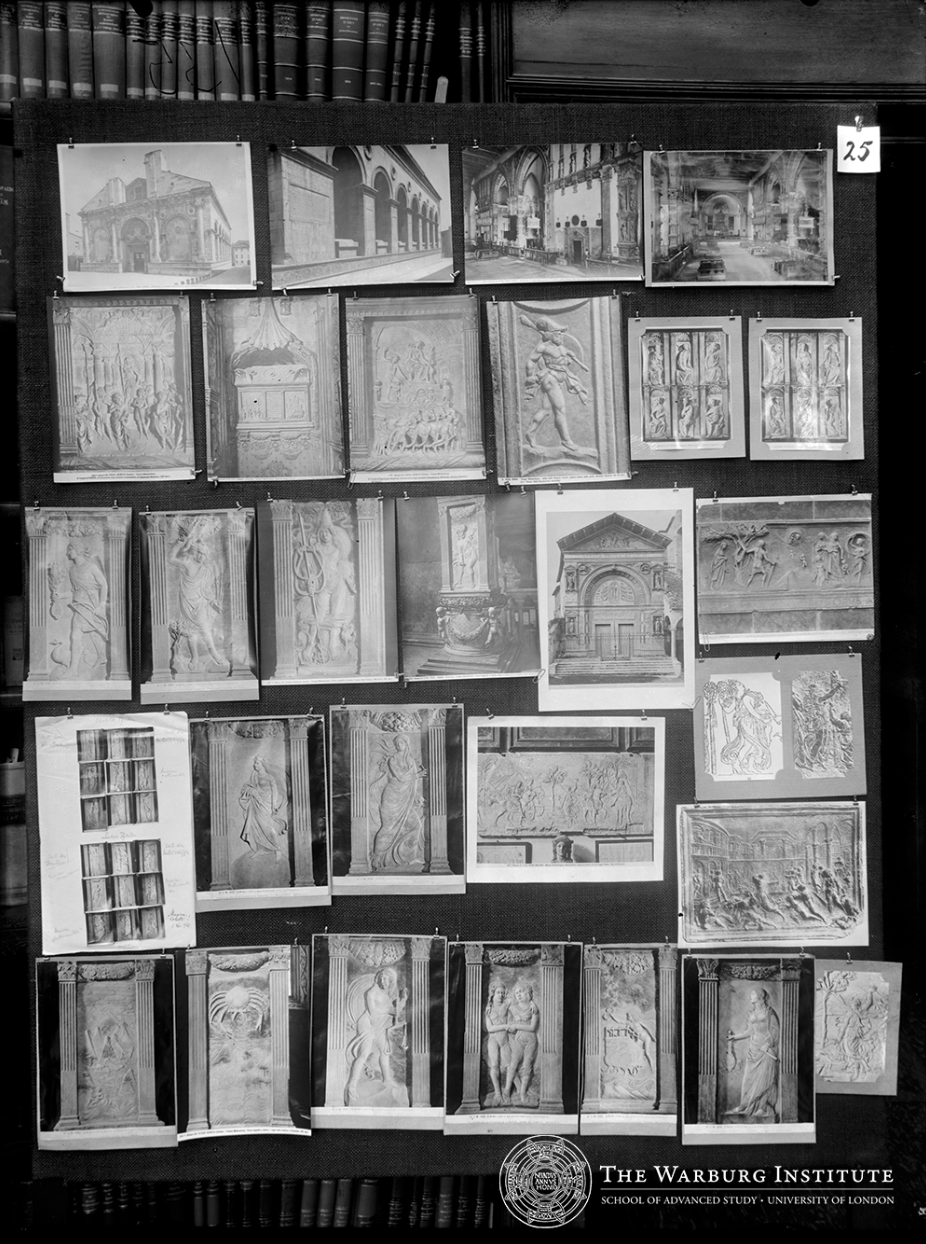

Fig. 2

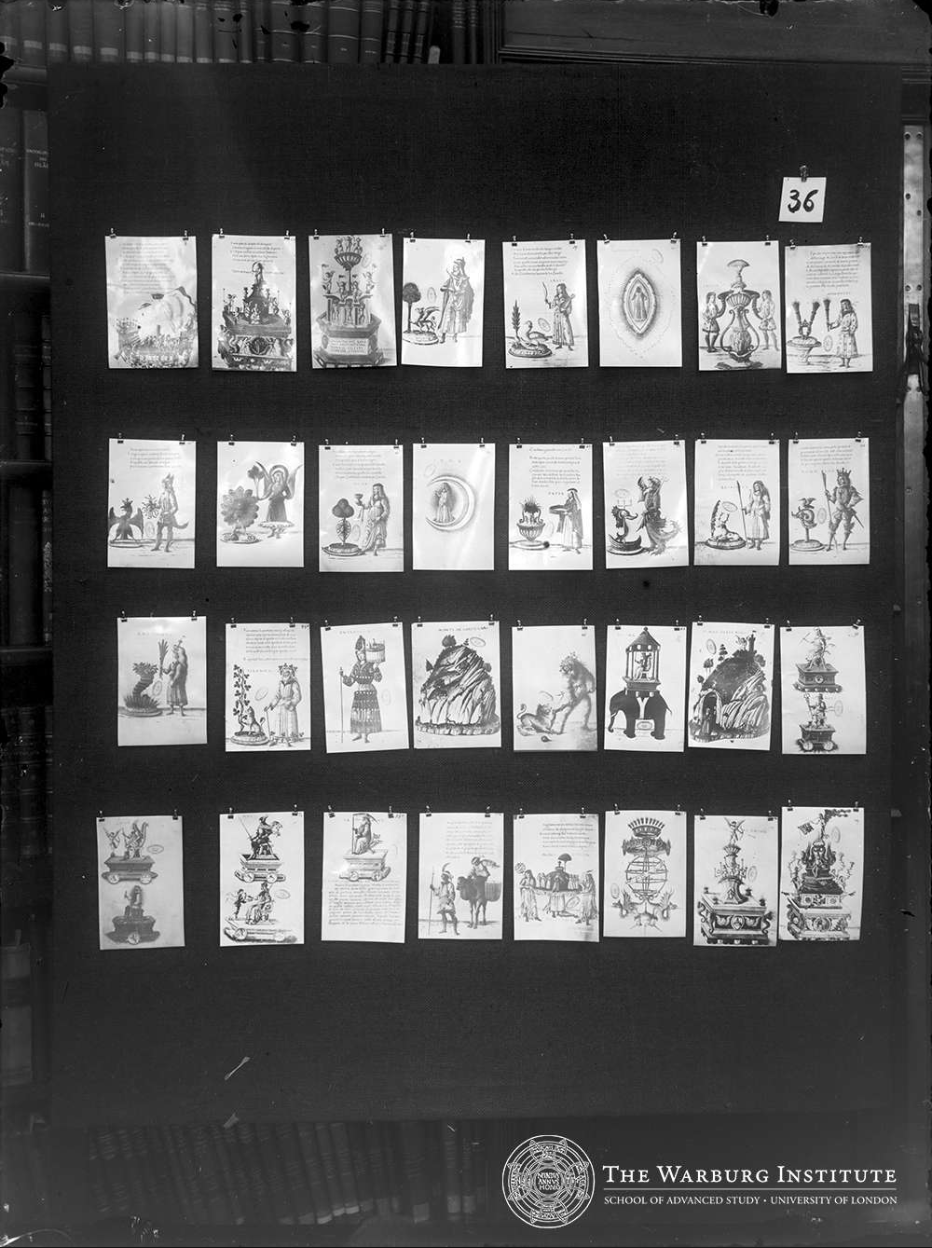

Fig. 3

Fig. 1 Theatre of Memory; Frances Amelia Yates, The Art of Memory, (London: Ark Paperbacks, 1984).

Fig. 2 Theatre of Memory; “Spatializing Knowledge: Giulio Camillo’s Theatre of Memory (1519-1544),” Socks Studio, March 3, 2019.

Fig. 3 L'idea del theatro (The Idea of the Theatre); “Spatializing Knowledge: Giulio Camillo’s Theatre of Memory (1519-1544),” Socks Studio, March 3, 2019.

At dusk, the wooden utility poles reeked of coal tar [8], a narrow alley where even shadows lay bent [9], a ditch down which black effluent once ran [10], and a bare red hill without a single tree [11], all strung across trivial and fragile places. Now we stand upon the sleek circular stage of the digital archive, and AI, grown to the size of Earth [12], rearranges the universe’s geometry with a cruelty of order. At the speed of reproducible images we forfeit the real. Perception lags.[13] My memory is no longer my own. This standardised memory[14] is now summoned as our collective memory. Benjamin spoke of memory’s fatal play.[15]

“What Proust began so playfully became awesomely serious. He who has once begun to open the fan of memory never comes to the end of its segments; no image satisfies him, for he has seen that it can be unfolded, and only in its folds does the truth reside.”[16]

The sea under the night-time factory lights at Masan [17] was a kind of mirror. The mirror kept cradling a new crane and with it another figure. Beneath its calm skin it hid the shadows of an old stone pier and forsaken nets. On today’s digital stage, the images reincarnated by AI show precisely such a double face. A command typed by the human hand is answered at once by the machine’s computation. Human choosing goes on as cutting and pasting. After the final scan, when the work hangs quietly upon the canvas, we overpaint seas and misted ridgelines older and stranger than we knew. In this translucent theatre, what is stored is less image than time, and less time than the trace of memory. Storage and display, past and future, gaze and data, keep overlapping. The panorama goes on swimming. The sky’s lens drops like an eyelid and rises again like a breath. Images generated by AI recall the rain-drenched mountains of my childhood and the pupil’s unrest. Some furrows of the iris carry, at once, today’s wrinkles and tomorrow’s fatigue. Memory branches into seams of light and at last pours into a vast lake.

[8] In Korean usage, the distinctive odor from creosote-treated utility poles and railway ties is commonly called “coal tar”, so the artist uses that familiar term—even though the preservative is technically creosote. Creosote, made by distilling tar from wood or coal, has been used to preserve wood since the mid-1800s. “Creosote,” US EPA, accessed August 13, 2025, https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/creosote.

[9] Referring to the alleyways of Sangnam-dong in Masan, the artist’s birthplace. “Administrative Districts,” Changwon City Hall, accessed August 13, 2025, https://www.changwon.go.kr/cwportal/eng/12659/12663/12670.web.

[10] With the industrialization of Masan after the establishment of MFTZ (see note 4) came the contamination of sea by garbage and industrial wastewater containing heavy metals, turning the water into the color of soy sauce. “Masan Bay/Pollution Site Investigation (Let's Save Our Environment),” The JoongAng, January 29, 1994, https://www.joongang.co.kr/article/2851857.

[11] An overarching term used by the artist for Yongmasan, Jebisan, and Mundisan. In particular, “Mundisan” is a colloquial place-name for a mountain said to have been home to people with Hansen’s disease. “Mundungi” (문둥이, lit. “leper”) historically referred to a person with Hansen’s disease; in the Gyeongsang dialect it appears as “mundi” (문디). The term is now considered stigmatizing. The artist recalls that, during childhood, rapid industrialization scarred the mountains around the family home and left them as bare red hills.

[12] A metaphor frequently used by the artist in lectures, describing AI as a planetary-scale reflective surface that mirrors human desires and projections. The artist has consistently voiced concern that AI, by storing human data and curating what people most want to see and hear, reinforces and often amplifies confirmation bias.

[13] “With the industrial proliferation of visual and audiovisual prostheses and unrestrained use of instantaneous-transmission equipment from earliest childhood onwards, we now routinely see the encoding of increasingly elaborate mental images together with a steady decline in retention rates and recall. In other words we are looking at the rapid collapse of mnemonic consolidation.” Paul Virilio, The Vision Machine (La machine de vision), trans. Julie Rose (Bloomington: IU Press, 1994) 6–7.

[14] In his article “Machine and Ecology,” Yuk Hui discusses AI and cybernetic totalization through synthetic collective memory. Yuk Hui, “Machine and Ecology,” in Cosmotechnics (London: Routledge, 2021), 54–66. See also Biao Xiang, “Grid Reaction: Comparing Mobility Restrictions during COVID-19 and SARS,” MoLab Inventory (Max Planck Institute), 2021, https://doi.org/10.48509/molab.5217.

[15] Benjamin disccuses the relationship between play and memory extensively, suggesting childhood play as a form of memory making and memory as play’s theatre. Walter Benjamin, Berlin Childhood around 1900 (Berliner Kindheit um neunzehnhundert), trans. Howard Eiland (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006).

[16] Walter Benjamin, One-Way Street and Other Writings (Einbahnstraße), trans. Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter (London: NLB, 1979), 295–296.

[17] On July 1st, 2010, Changwon, Masan, and Jinhae were integrated as Changwon City. (“History,” Changwon City Hall, accessed August 13, 2025, https://www.changwon.go.kr/cwportal/eng/12659/12663/12668.web.) Masan, the artist’s hometown, had once developed into a city of approximately 500,000 residents, but following its administrative incorporation into Changwon, its name effectively disappeared, as though rendered obsolete.

[9] Referring to the alleyways of Sangnam-dong in Masan, the artist’s birthplace. “Administrative Districts,” Changwon City Hall, accessed August 13, 2025, https://www.changwon.go.kr/cwportal/eng/12659/12663/12670.web.

[10] With the industrialization of Masan after the establishment of MFTZ (see note 4) came the contamination of sea by garbage and industrial wastewater containing heavy metals, turning the water into the color of soy sauce. “Masan Bay/Pollution Site Investigation (Let's Save Our Environment),” The JoongAng, January 29, 1994, https://www.joongang.co.kr/article/2851857.

[11] An overarching term used by the artist for Yongmasan, Jebisan, and Mundisan. In particular, “Mundisan” is a colloquial place-name for a mountain said to have been home to people with Hansen’s disease. “Mundungi” (문둥이, lit. “leper”) historically referred to a person with Hansen’s disease; in the Gyeongsang dialect it appears as “mundi” (문디). The term is now considered stigmatizing. The artist recalls that, during childhood, rapid industrialization scarred the mountains around the family home and left them as bare red hills.

[12] A metaphor frequently used by the artist in lectures, describing AI as a planetary-scale reflective surface that mirrors human desires and projections. The artist has consistently voiced concern that AI, by storing human data and curating what people most want to see and hear, reinforces and often amplifies confirmation bias.

[13] “With the industrial proliferation of visual and audiovisual prostheses and unrestrained use of instantaneous-transmission equipment from earliest childhood onwards, we now routinely see the encoding of increasingly elaborate mental images together with a steady decline in retention rates and recall. In other words we are looking at the rapid collapse of mnemonic consolidation.” Paul Virilio, The Vision Machine (La machine de vision), trans. Julie Rose (Bloomington: IU Press, 1994) 6–7.

[14] In his article “Machine and Ecology,” Yuk Hui discusses AI and cybernetic totalization through synthetic collective memory. Yuk Hui, “Machine and Ecology,” in Cosmotechnics (London: Routledge, 2021), 54–66. See also Biao Xiang, “Grid Reaction: Comparing Mobility Restrictions during COVID-19 and SARS,” MoLab Inventory (Max Planck Institute), 2021, https://doi.org/10.48509/molab.5217.

[15] Benjamin disccuses the relationship between play and memory extensively, suggesting childhood play as a form of memory making and memory as play’s theatre. Walter Benjamin, Berlin Childhood around 1900 (Berliner Kindheit um neunzehnhundert), trans. Howard Eiland (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006).

[16] Walter Benjamin, One-Way Street and Other Writings (Einbahnstraße), trans. Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter (London: NLB, 1979), 295–296.

[17] On July 1st, 2010, Changwon, Masan, and Jinhae were integrated as Changwon City. (“History,” Changwon City Hall, accessed August 13, 2025, https://www.changwon.go.kr/cwportal/eng/12659/12663/12668.web.) Masan, the artist’s hometown, had once developed into a city of approximately 500,000 residents, but following its administrative incorporation into Changwon, its name effectively disappeared, as though rendered obsolete.

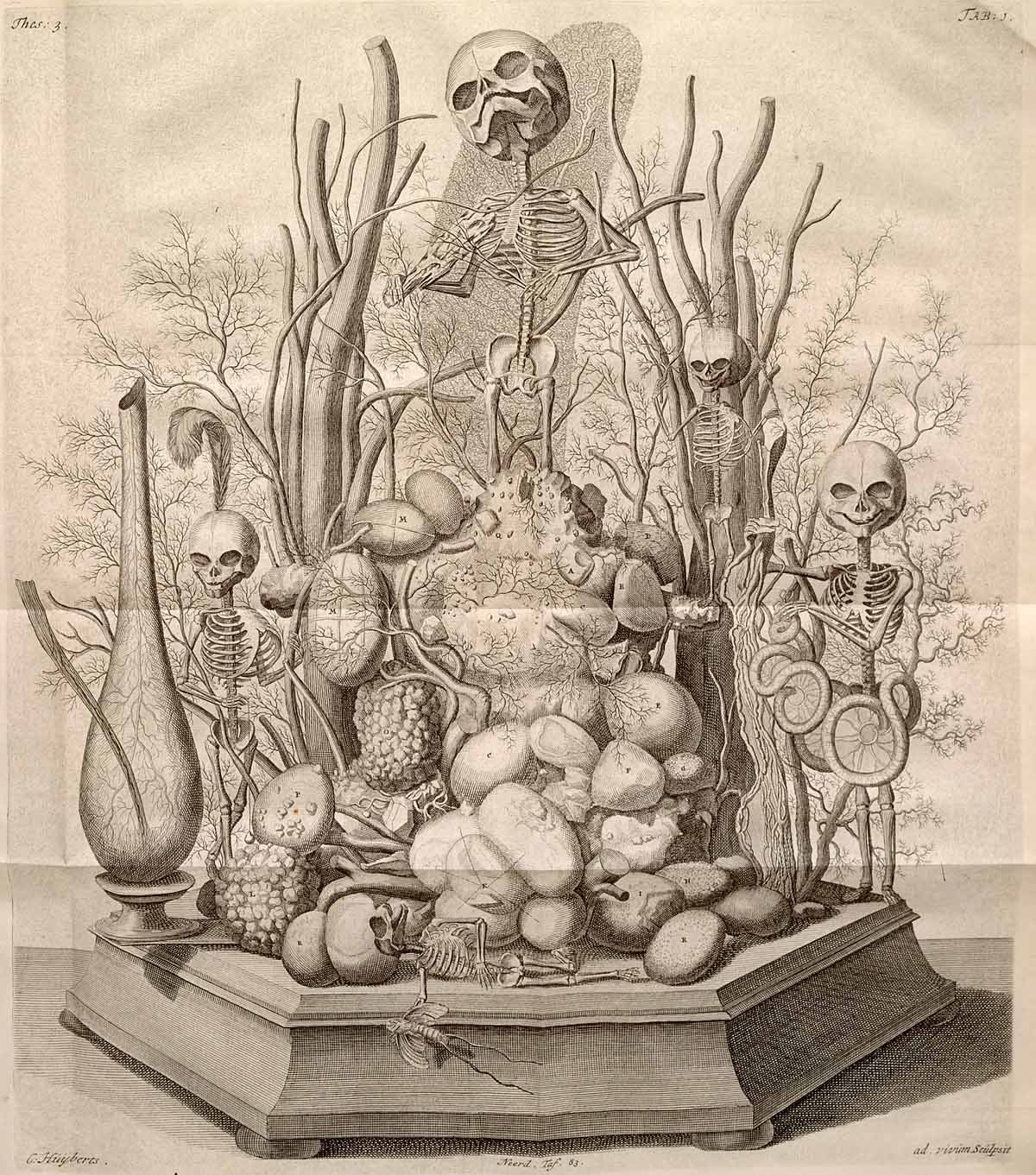

Fig. 4

Fig. 4 Masan’s nightscape with the lights of factories; Changwon City,

“The Night View of Masan (Hoewon-gu. Happo-gu) from Muhaksan Mountain,” Naver Blog, February 6, 2017.

Why do we remember?

To translate one bodily organ into another sense is to synaesthetically anatomise [18] the memories of a translucent body. The iris’s minute pleats and the pixels’ subtle tints are no longer a mute surface. They become a score the ear can read, and the private abstracts itself and tangles into anonymous resonance. An iris rendered into sound is no longer someone’s eye. Sound, vanishing into air, reveals an impersonal materiality, and the personal and the anonymous co-inhabit. The revolving inner cosmos is called outward for a moment and then disappears again into the outer cosmos. Laid upon this turntable, the iris of AI is translated once more and heard. With each revolution, sound and silence, born together, reveal both the self who logs in and the fate that will one day log out. The dust of memory returns to an origin that holds the universe’s blank, and the trajectories of questions are drawn, ceaselessly, as landscape.

[18] The artist employs the neologism synaesthetic dissection to describe how AI interprets, cross-maps, and reconfigures human sensory experience. Synaesthesia is a condition in which one property of a stimulus evokes a second experience not ordinarily associated with the first—for example, taste eliciting an experience of colour (Michael J. Banissy et al., “Synesthesia: an introduction,” Frontiers in Psychology 5 (2014): 1414, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01414). For a historical analogue, see Frederik Ruysch (1638–1731), a Dutch professor of anatomy and botany renowned for his collection of preserved specimens and his meticulous technique of post-mortem vascular injections; his mercuric sulphide–based injection mixtures imparted a reddish, almost lifelike appearance to tissues (Lucas Boer, “Frederik Ruysch (1638–1731): Historical perspective and contemporary analysis of his teratological legacy,” American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 173, no. 1 (2017): 16–41, https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.37663). He arranged his anatomical specimens in vanitas-like tableaux, thereby uniting scientific precision with symbolic meditations on the finitude of human existence.

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 5 “Ah Fate, ah Bitter Fate!” An etching from Thesaurus anatomicus; “The Bizarre 17th-Century Dioramas Made from Real Human Body Parts,” Atlas Obscura, November 17, 2016.

Fig. 6 A preserved human hand holds hatching reptile in one jar, and in another is a floating fish. Both are topped with elaborate displays of shells, corals, and plants; “The Bizarre 17th-Century Dioramas Made from Real Human Body Parts,” Atlas Obscura, November 17, 2016.

Fig. 7 Part of injected mucous esohagus on a tree branch. Fr. Ruysch’s specimen. Late 17th-early 18th c. Holland; “Acquisition of collections in Europe: Frederik Ruysch, Albert Seba, Joseph-Guichard Duverney,” Kunstkamera, accessed August 18, 2025.

Fig. 8 Portrait of Frederik Ruysch at the age of 85, copperplate. Jan Wandelaar, 1723; Lucas Boer, “Frederik Ruysch (1638–1731): Historical perspective and contemporary analysis of his teratological legacy” American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 173, no. 1 (2017): 16–41.

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Fig. 9 Museum Vrolik’s lung tissue specimens injected with colored wax, a technique first used by Frederik Ruysch; Museum Vrolik, Facebook, April 3, 2025.

Fig. 10 Corrosion cast of a kidney; “Key Object Page,” Surgeons’ Hall Museums, accessed August 18, 2025.

The medium is memory [19]

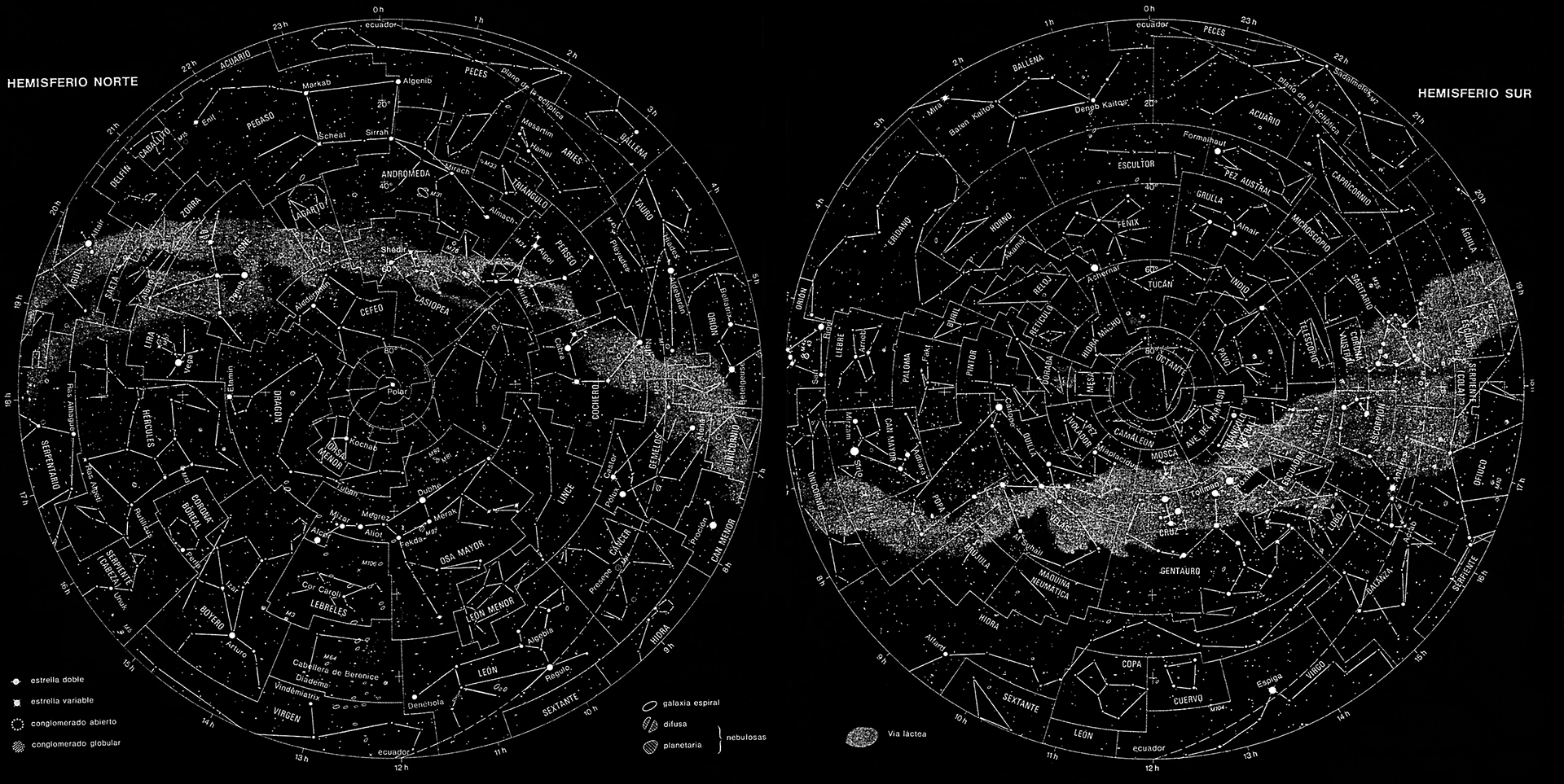

A certain practitioner in India once read the universe inscribed upon my iris and whispered, “Here, your former lives and the metempsychosis of humankind are superimposed.”[20] Within the iris, after-images of ancient cave paintings and this morning’s short-form video make a collage. My body, made transparent, can no longer be found. I vanished long ago upon the stage of memory. In the distance a ridge rises again, holding a turquoise afterglow, and somewhere at its foot old hills and lakes ripple like clusters of data. Warburg’s vast memory-board [21] is rewoven now by algorithms. This theatre cradles a surveillance camera [22] without an observer. Angels, ophanim [23], hang in the air, their wheels full of eyes, and metallic wavelengths of light bind spirit, code, and pixel into a single breath, becoming the eighty-eight constellations.[24] The stage darkens. The auditorium is silent. Yet the wheel within the wheel does not stop, and we begin again forever as part of its trajectory. Outside the eye, another eye opens. The cornea of a colossal iris hangs in the air and peers into me like the round heavens that once promised Renaissance salvation.[25] Memory develops without phenomena, and the spectator, captive to speed, stands trial. The narratives of the past that were storehouses of memory now do nothing but await oblivion amid the excess of real-time feeds.[26] In this high-velocity interstice, where even private suffering becomes content, I draw a breath and leave a slow brushstroke.[27] Boundaries blurred by gesture, low-resolution and emptied, are overpainted only with our own images. The aura of a new digital algorithm [28] is generated in the repetition of the “now-here”[29], and the same lines, passing through ‘Nine Reincarnations’[30], complete a voice.

[19] “The medium is the memory.” Rosalind E. Krauss, Under Blue Cup (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2011), 3

[20] While in India, a spiritual practitioner read memories of the past life and wounds of the body and mind through the artist’s iris.

[21] Bilderatlas Mnemosyne was one of German art historian Aby Moritz Warburg’s most famous works. Never completed, it was a series of black panels covered with clusters of images of all sorts, with both the number of panels and curation of images constantly changing. “Bilderatlas Mnemosyne,” The Warburg Institute, accessed August 12,, 2025, https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/archive/bilderatlas-mnemosyne.

[22] In 2017, visual artist Xu Bing released his film Dragonfly Eyes. As a fictional narrative of a woman living in China made through the stitching together of surveillance footage, the work explored the relationship between vision and meaning, between fragments of real life and ‘reality.’ “MoMA Presents Xu Bing’s Dragonfly Eyes,” MoMA, accessed August 13, 2025, https://www.moma.org/calendar/film/5009. “Projects,” Xu Bing, accessed August 13, 2025, https://www.xubing.com/en/work/details/469?type=project

[23] The advancement of generative AI has made possible vivid visualizations of ideas once only imagined or drawn, inducing awe among people. An example is AI depictions of Ophanim from the Bible, a living creature with characteristics like “whirling wheels” completely full of eyes. (Ezek. 1:15-21, 10:9-17 (NIV).) An Instagram post included a video of AI-generated Ophanim and referred to them as “Biblically Accurate Angels.” The AI Bible (@theaibibleofficial), “Biblically Accurate Angels”, Instagram, December 24, 2023, https://www.instagram.com/reel/C1NKOTEvn0j/?hl=en.

[24] The International Astronomical Union(IAU) recognizes a list of 88 constellations. “The Constellations,” International Astronomical Union, accessed August 12, 2025, https://iauarchive.eso.org/public/themes/constellations/.

[25] The Assumption of the Virgin is a painting by Francesco Botticini, of Christ blessing the Virgin Mary who has ascended after death into a place full of clouds and golden light, visualized as a dome-shaped vault opened up in the sky in a depiction of unified heaven and earth. “The Assumption of the Virgin,” The National Gallery, accessed August 12, 2025, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/francesco-botticini-the-assumption-of-the-virgin.

[26] Paul Virilio, through his concept of dromology—the logic of speed—, discusses how the acceleration of speed driven by technology impacts society. (Virilio, Speed and Politics (Vitesse et Politique), trans. Marc Polizzotti (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006).) “The development of high technical speeds would thus result in the disappearance of consciousness as the direct perception of phenomena that inform us of our own existence.” Paul Virilio, The Aesthetics of Disappearance (Esthétique de la disparition), trans. Philip Beitchman (New York: Semiotext(e), 1991), 104.

[27] A slow brushstroke, as a first-mile gesture, rebuilds the nearby by re-binding relations at the edges of everyday life. (Biao Xiang, “The Nearby: A Scope of Seeing,” Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art 8, nos. 2–3 (2021): 147–165, https://doi.org/10.1386/jcca_00042_1.) “The nearby brings different positions into one view, thus constituting a ‘scope’ of seeing.”

[28] These images circulate everywhere and nowhere, simultaneously; they are Benjaminian Jetztzeit rendered as pure data-packet. Kris Belden-Adams, “Theorizing the Ubiquitous, Immaterial, Post‑digital Photograph via Benjamin and Baudelaire,” in Reproducing Images and Texts (la Reproduction des Images et des Textes), ed. Kirsty Bell and Philippe Kaenel (Leiden: Brill, 2021), 57–66. Kris Belden-Adams, “Everywhere and Nowhere, simultaneously: Theorizing the Ubiquitous, Immaterial, Post‑Digital Photograph,” in Mobile and Ubiquitous Media: Critical and International Perspectives, ed. Michael S. Daubs and Vincent R. Manzerolle (New York: Peter Lang, 2017), 163–179.

[29] In his essay, Benjamin explicitly mentions Jetztzeit: “History is the subject of a structure whose site is not homogenous, empty time, but time filled by the presence of the now. [Jetztzeit].” (Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History (Über den Begriff der Geschichte),” in Critical theory and society, ed. Stephen Eric Bronner and Douglas MacKay Kellner (London: Routledge, 2020), 255-263.) Jetztzeit, translated as ‘now-time’ and ‘time of the now’ is further defined as “an explosive [Explosivstojf] to which historical materialism adds the fuse. The aim is to explode the continuum of history with the aid of a conception of historical time that perceives it as ‘full’, as charged with ‘present’, explosive, subversive moments.” Michael Löwy, Fire Alarm: Reading Walter Benjamin's ‘On the concept of history,’ trans. Chris Turner (London: Verso, 2005), 87–88.

[30] ‘Nine Reincarnations’ refers to the artist’s nine-stage workflow for the 2025 hybrid, post-digital collage-painting series On Some Faraway Shore, framed as a recursive gesture in which source images are repeatedly translated between digital and physical media—from data curation and AI synthesis, through printing, hand collage, re-digitisation, compositing, and under-printing on canvas, to final painterly interventions—so that the output of each pass feeds back as input to the next, constituting a ‘rebirth’ of the image.

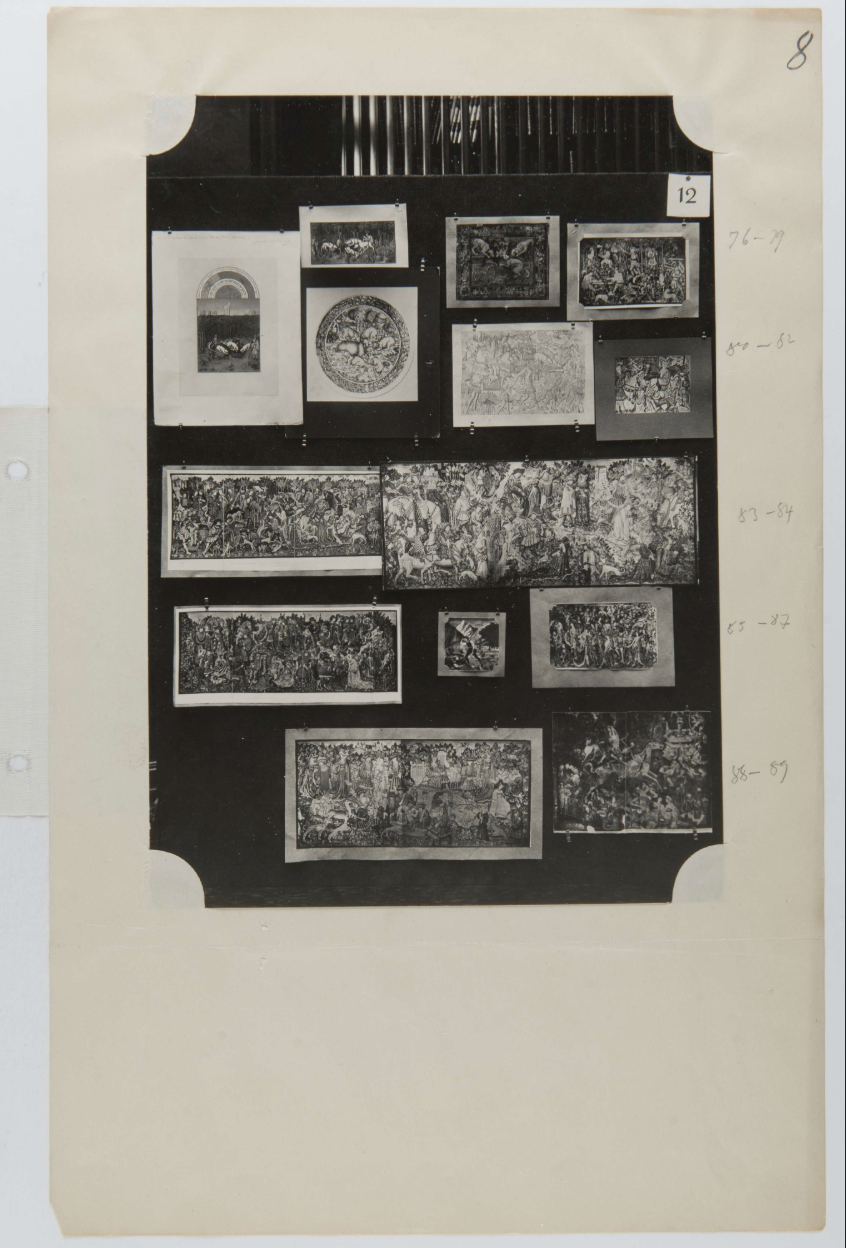

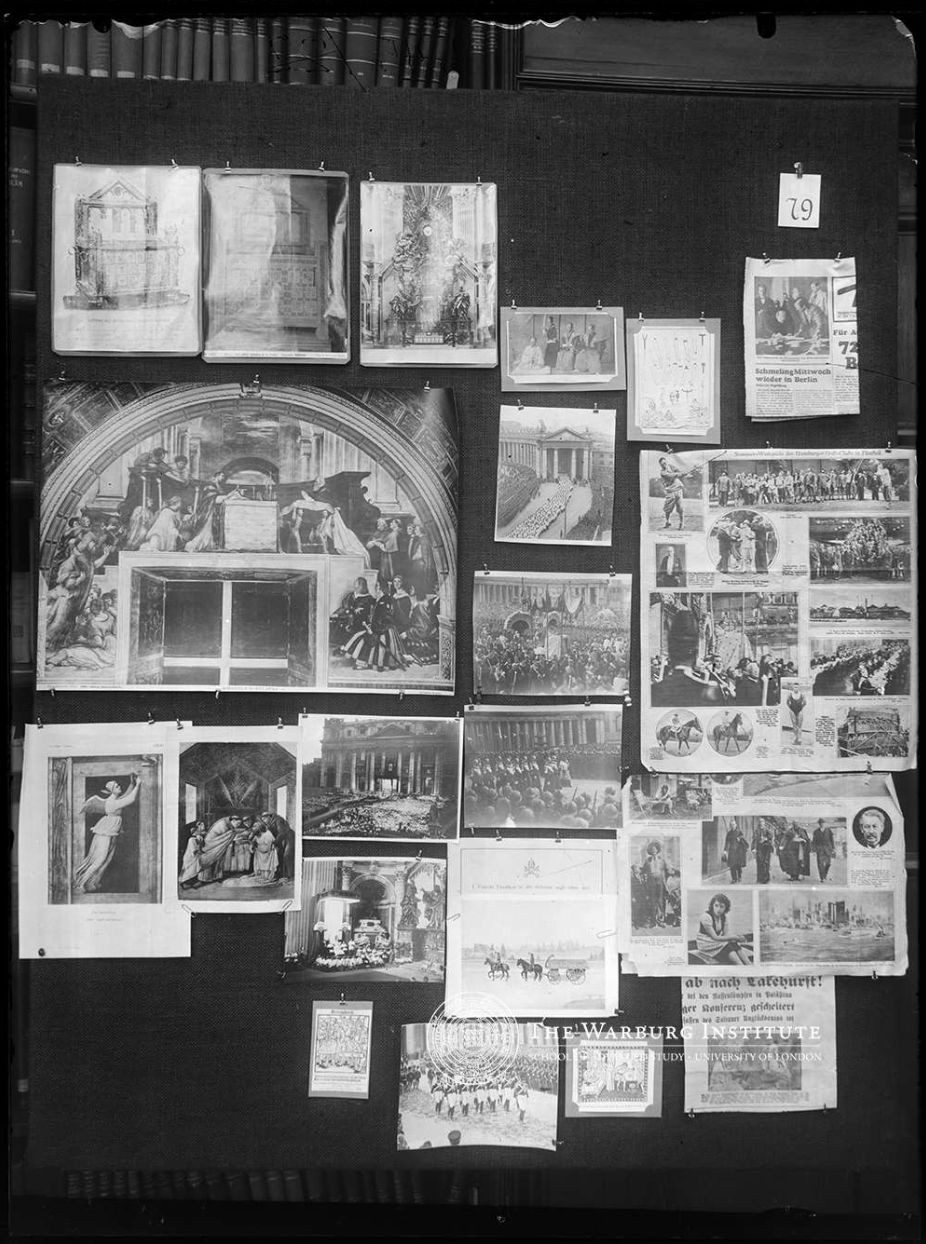

Fig. 11 Panel 1, 8, 10, 26 of the First Version; “Bilderatlas Mnemosyne | First version,” The Warburg Institute, accessed August 12,, 2025.

Fig. 12 Panel 8, 29, 41, 54 of the Penultimate Version; “Bilderatlas Mnemosyne | Penultimate version,” The Warburg Institute, accessed August 12,, 2025.

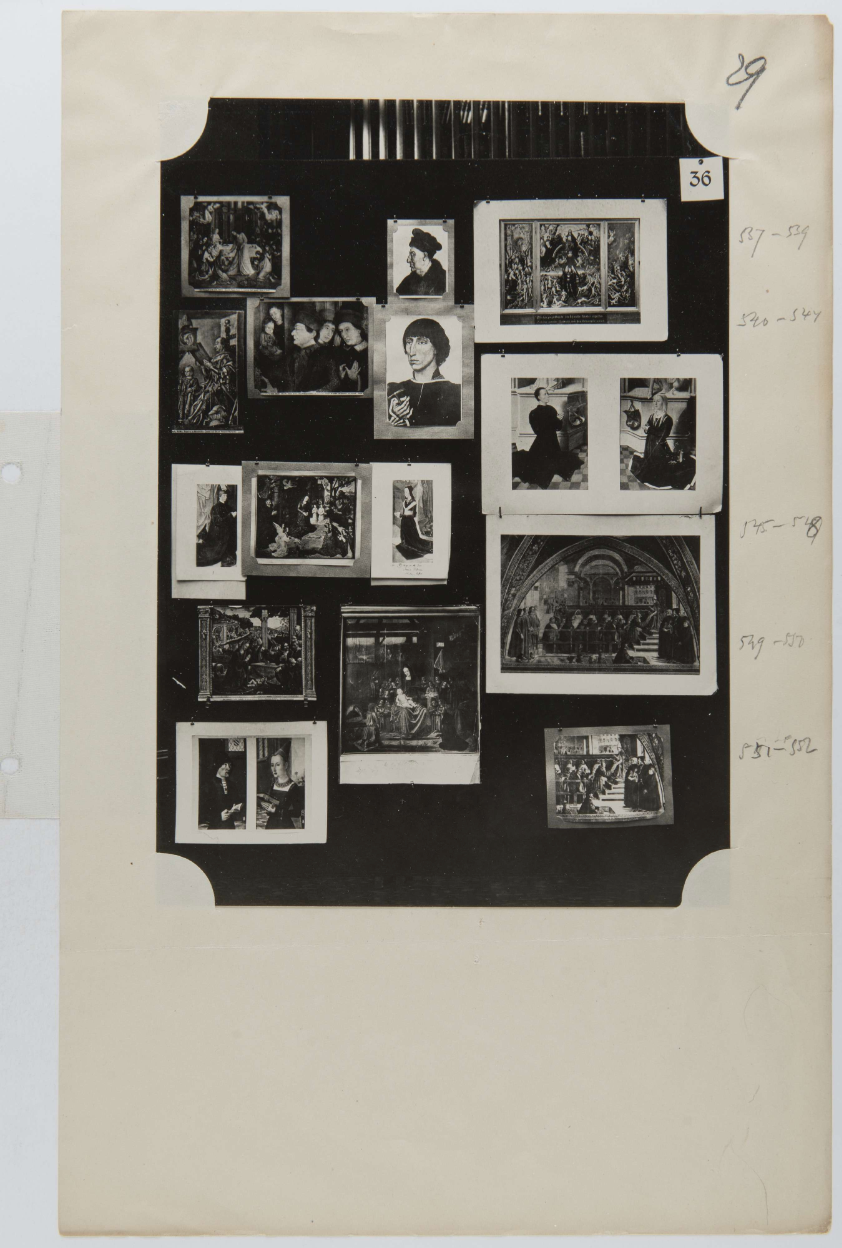

Fig. 13 Panel 2, 25, 36, 79 of the Final Version; “Bilderatlas Mnemosyne | Final version,” The Warburg Institute, accessed August 12, 2025.

Fig. 15

Fig. 16-1

Fig. 16-2

Fig. 14 Dragonfly Eyes; “Projects,” Xu Bing, accessed August 13, 2025.

Fig. 15 An array of images obtained through KAIST’s ultra-thin, high-resolution camera (left). A composite image synthesized from these images (right); “High-Resolution Camera Lens that Mimics Fly’s Eye,” Nate News, April 13, 2020.

Fig. 16 Dragonfly eyes and virtual eyes; “Amazing Animal Eyes,” Village Optical, July 23, 2013. (top), “Apple Vision Pro customer interests now appears to be fading away,” GizChina, April 22, 2024. (bottom)

Fig. 17

Fig. 18

Fig. 19

Fig. 17 AI generated Ophanim; “Ophanim,” Bible Wiki, accessed August 18, 2025.

Fig. 18 The Assumption of the Virgin by Francesco Botticini; “The Assumption of the Virgin,” The National Gallery, accessed August 12, 2025.

Fig. 19 Engraved illustration of the "chariot vision" of the Biblical book of Ezekiel, chapter 1, after an earlier illustration by Matthaeus (Matthäus) Merian (1593-1650), for his "Icones Biblicae" (a.k.a. "Iconum Biblicarum"); “File: Ezekiel’s vision.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, accessed August 18, 2025.

Input by human → generation by AI → selection by human → printing by AI → cutting by human → collage, pasting by human → scan by AI → underprinting by AI → brushwork by human

At last, things infinitely fast resolve into stillness and vast noise converges into quiet.[31] This is the moment when Baudelaire sought to seize eternity within transience[32], like a supernova’s afterglow millions of light-years away seeping into the pupil. At last, a long-dormant memory, folded within the fan, leaps up in fine effervescence and a cosmic detonation.

At last, things infinitely fast resolve into stillness and vast noise converges into quiet.[31] This is the moment when Baudelaire sought to seize eternity within transience[32], like a supernova’s afterglow millions of light-years away seeping into the pupil. At last, a long-dormant memory, folded within the fan, leaps up in fine effervescence and a cosmic detonation.

“Champagne Supernova.”[33]

[31] Henri Bergson’s concept of duration is the continuous flow of subjective experience and consciousness that is distinctive from objective time. “Pure duration is the form which the succession of our conscious states assumes when our ego lets itself live, when it refrains from separating its present state from its former states.” (Henri Bergson, Time and Free Will (Essai sur les données immédiates de la conscience), trans. F. L. Pogson, M. A. (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2001), 100.) While Bergson suggest that such flows lead to creativity, Virilio suggest that technological speed inverts such processes, producing stasis and halting creative emergence. Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution (L’Évolution créatrice), trans. Arthur Mitchell (New York: Henry Hold and Company, 1911); Paul Virilio, The Aesthetics of Disappearance.

[32] Charles Baudelaire, "The Painter of Modern Life (Le Peintre de la vie moderne)," in Modern Art and Modernism (London: Routledge, 2018), 23–28.

[33] "Champagne Supernova," track 5 on (What's the Story) Morning Glory?, by Oasis, Creation Records, 1995

[32] Charles Baudelaire, "The Painter of Modern Life (Le Peintre de la vie moderne)," in Modern Art and Modernism (London: Routledge, 2018), 23–28.

[33] "Champagne Supernova," track 5 on (What's the Story) Morning Glory?, by Oasis, Creation Records, 1995

Fig. 20-1

Fig. 20-2

Fig. 20 Iridology chart © 1985, Harris Wolf, MA.; Yosef Ben, “Finnish Eye Chart Instructions,” Pinterest, accessed August 18, 2025. (left), “Irisdiagnose,” E-stilo.net, accessed August 18, 2025. (right)

Fig. 21

Fig. 21 Celestial chart, list of 88 constellations in the night sky is divided; “File:Celestial chart (asterisms and areas) (esp).png,” Wikimedia Commons, March 28, 2008.

Fig. 22

Fig. 22 Iris; “Anatomical and physiological structure of the eye,” The Korean Iridology and Medical Association, accessed August 18, 2025.

Bibliography

The AI Bible. “Biblically Accurate Angels.” Instagram, December 24, 2023.

Banissy, Michael J., et al. “Synesthesia: An Introduction.” Frontiers in Psychology 5 (2014): 1414.

Baudelaire, Charles. "The Painter of Modern Life.” In Modern Art and Modernism. London: Routledge, 2018.

Belden-Adams, Kris. “Everywhere and Nowhere, Simultaneously: Theorizing the Ubiquitous, Immaterial, Post-Digital Photograph,” In Mobile and Ubiquitous Media: Critical and International Perspectives, edited by Michael S. Daubs and Vincent R. Manzerolle, 163–179. New York: Peter Lang, 2017.

________________. “Theorizing the Ubiquitous, Immaterial, Post-Digital Photograph via Benjamin and Baudelaire.” In Reproducing Images and Texts, edited by Kirsty Bell and Philippe Kaenel, 57–66. Leiden: Brill, 2021.

Benjamin, Walter. Berlin Childhood around 1900. Translated by Howard Eiland. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

______________. One-Way Street and Other Writings. Translated by Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter. London: NLB, 1979.

______________. “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” In Critical Theory and Society, edited by Stephen Eric Bronner and Douglas MacKay Kellner, 255–263. London: Routledge, 2020.

Bergson, Henri. Creative Evolution. Translated by Arthur Mitchell. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1911.

____________. Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness. Translated by F. L. Pogson. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2001.

Boer, Lucas. “Frederik Ruysch (1638–1731): Historical Perspective and Contemporary Analysis of His Teratological Legacy.” American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 173, no. 1 (2017): 16–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.37663.

Brecht, Bertolt. Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic. Edited and translated by John Willett. London: Eyre Methuen, 1974.

Changwon City Hall. “Administrative Districts.” Accessed August 13, 2025.

________________. “History.” Accessed August 13, 2025.

International Astronomical Union. “The Constellations.” Accessed August 12, 2025.

JoongAng Ilbo. “Masan Bay/Pollution Site Investigation (Let’s Save Our Environment).” January 29, 1994.

Karatani, Kōjin. Origins of Modern Japanese Literature. Translated by Brett de Bary. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993.

Krauss, Rosalind E. Under Blue Cup. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011.

Lee, Julian Jinjoon. Nowhere in Somewhere. Seoul: Marmmo Press, 2023.

Löwy, Michael. Fire Alarm: Reading Walter Benjamin’s “On the Concept of History.” Translated by Chris Turner. London: Verso, 2005.

Masan Free Trade Zone Office. “About MFTZ.” Accessed August 13, 2025.

National Gallery. “The Assumption of the Virgin.” Accessed August 12, 2025.

Oasis. “Champagne Supernova.” Track 5 on (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? London: Creation Records, 1995.

Rancière, Jacques. The Emancipated Spectator. Translated by Gregory Elliott. London: Verso, 2011.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “Creosote.” Accessed August 13, 2025. https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/creosote.

Virilio, Paul. The Aesthetics of Disappearance. Translated by Philip Beitchman. New York: Semiotext(e), 1991.

_________. Speed and Politics. Translated by Marc Polizzotti. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006.

_________. The Vision Machine. Translated by Julie Rose. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Warburg Institute. “Bilderatlas Mnemosyne.” Accessed August 12, 2025.

Xu Bing. “Projects: Dragonfly Eyes.” Accessed August 13, 2025.

Xiang, Biao. “Grid Reaction: Comparing Mobility Restrictions during COVID-19 and SARS.” MoLab Inventory, 2021.

_________. “The Nearby: A Scope of Seeing.” Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art 8, nos. 2–3 (2021): 147–165.

Yates, Frances A. The Art of Memory. London: Ark Paperbacks, 1984.

Yuk Hui. “Machine and Ecology.” In Cosmotechnics, 54–66. London: Routledge, 2021.

九度の転生 [1]

ポストAI時代における記憶の再構成

イ・ジンジュン

ポストAI時代における記憶の再構成

イ・ジンジュン

本稿は、記憶・イメージ・AI・感覚が交錯する地点で生まれる、存在論的かつ美学的な体験を解き明かす詩的散文である。それは、東アジアを基盤とする同時代のメディア哲学の一断面であると同時に、ひとつの実践的提案でもある。伝統的な批評や学術論文の形式とは異なり、詩のリズムと哲学の構造が交差する地形の上で書かれたこのテクストは、筆者が長年探求してきた「境界空間(liminality)」的感受性に基づいている。すなわちそれは、ポストデジタル時代における記憶を再構成するための感覚的な旅であり、同時代の文人芸術家(artist-scholar)による書きものでもある。このテクストは、人文学・詩学・メディアアートの領域を横断しながら、「記憶―イメージ―機械―自己叙述」をひとつの実験的記憶装置として編纂する。脚注や引用、図版を自在に行き来しながら、読者と私的に向き合おうとするこの文章のリズムによって、概念と感覚が並走する言語的風景を描き出す。この流れに身を委ねながら、「折りたたまれた記憶という扇を、もう一度開く感覚」を、読者が自身の身体のなかで再び感じ取ってくれることを願う。

私は「置かれている [2]」

虹彩を通じてログインした私は、名も知れぬ巨大な「記憶の劇場 [3]」に置かれていた。そこは湖の深淵のように黒く沈み、天井にあるもうひとつの視線が、私を映している。無数のイメージで構成された層――それぞれ異なる記憶たち――が、ゆっくりと、そして壮大に回転している。視線はもはや私のものではなく、彼らのものだ。ひとつの場面が次の場面へと滑り込むとき、「それ」はもはや「それ」ではなくなり、ひとつの「風景」となる [4]。私が見つめているものがまた、私のことも見返す。この「記憶の劇場」の上に、私はこうして置かれている。

心をひとすじ引き抜き、どこか一点を凝視しようとしても、焦点はたえずずれ、上滑りしていく。この緩慢な眩暈は、かつて故郷の海辺で風が頬をかすめたときに感じた、あの解放感を思い出させる。あの頃、私は水平線を滑る陽の光を追いかけ、錆びついた鉄橋の前でよく立ち止まった。足元に溜まった海水は、夏には石鹸の泡にまじる潮の匂いを、冬には厚いエナメルのような冷気を含んでいた。埠頭の向こうからいつも立ち上る煙突の煙は、「輸出自由地域 [5]」の「自由」という言葉を、微妙な嗅覚の記憶とともに呼び起こす。果たして機械は私たちの代わりに、あの磯とエナメルが混ざり合う匂いまでも、記憶することができるのだろうか。この、ほとんど無限に近いが有限の記憶装置は、現実よりも高解像度のイメージとして、私たちの前に召喚されるときを待っている。イメージの過剰のなかで、私のあの脆弱な記憶は、つくられた瞬間にすぐ蒸発してしまう。それでも記憶へのもがきこそが、記憶を呼び戻すための技術ではなかっただろうか。

紀元前5世紀、ギリシアの詩人シモーニデース(Simonides [6])は、天井が崩落した宴会場のなかで、空間の配置を手がかりに判別のつかなくなった遺体を識別してみせたという。古代の雄弁家たちは、日々変わる演説を、一時的に借りた建物や通りといった仮初の脆弱な場所を「記憶の宮殿 [7]」として用い、そこで練習を重ねた。また、ルネサンスの哲学者ジュリオ・カミッロ(Giulio Camillo [8])は、人々の持つ記憶を一望することができる円形劇場を構想し、その舞台にひとりの人間を招き入れた。それは、時を経ても摩耗することのない真理、そして言葉によって表現され得るあらゆる本質を、永遠に封じ込めんとする理想であった。不変の宇宙における象徴的秩序を宿すこの「記憶の劇場」は、いつでも永遠の真理を呼び出せるよう設計されていた。夕暮れ時、コールタールの匂いを放つ木製の電信柱 [9]、影が伸びることすらなく横たわる狭い路地 [10]、黒い廃水が流れ落ちていた小川 [11]、そして――本の木もない赤茶けたはげ山 [12]――。そうした、取るに足らない脆弱な場所が、置かれている。そしていま、私たちはデジタル・アーカイブという滑らかな円形の舞台の上に置かれ、地球規模にまで膨張したAI [13] が、残酷なまでに秩序立ったやり方で、宇宙の幾何学を再構成している。複製可能なイメージの速度のなかで、私たちは「実在」を喪失し、知覚は遅延として立ち上がる [14]。私の記憶はもはや私自身のものではない。標準化されたこの記憶は、いまや私たちの集合的記憶 [15] として召喚されるのだ。ヴァルター・ベンヤミンは、記憶の致命的な遊戯 [16] について次のように語った。

プルーストがなんとなく遊び半分に始めたことは、息もつかせぬ真剣負になった。いったん想〞の扇を広げ始めた者は、つねに新しい肢節、新しい骨を見出す。いかなるイメージも、彼には充分ではない。というのも、彼はイメージは展開されるべきものだ、ということを認識したのだから。まずもって襞のなかにこそ、本来的なもの――あのイメージ、あの味、あの手触り――が住みついているのだ [17]。

馬山(マサン [18])の夜、工場の灯りの下で見た海は、一枚の鏡のようであった。いつも新しいクレーンを鏡面にたたえ、別の形象として生まれ変わりながらも、穏やかな水面の下に、古びた石造りの埠頭と廃漁網の影を深く隠していた。今日、デジタルの舞台でAIが転生させたイメージは、まさにこうした二つの顔を露わにする。人間の手によって入力された指令は、すぐさま機械の演算へと変換され、人間の選択は再び切り貼りの作業として続いていく。そして最終のスキャンを経て静かにキャンバスの上に吊るされるとき、私たちはそこに、自らが知っていたよりもはるかに古く、そしてはるかに見知らぬ海と霧のなかの山稜を塗り重ねているのだ。この半透明の劇場に保存されているのは、もはやイメージというより時間、さらには時間というより記憶の痕跡である。保存と展示、過去と未来、視線とデータは、絶えず重なり合う。パノラマはいまもなお遊泳し、空のレンズはまぶたのように降りては、呼吸するかのように再び擡げられる。AIが生成したイメージは、幼い頃に見た、水に濡れた山々と瞳の不安に似ている。虹彩のなかのいくつかの皺は、いまの私の皺と、明日の疲労を同時に宿している。記憶は無数の鉱脈へと分かれ、ついにはひとつの巨大な湖へと流れ込んでいく。

我々はなぜ記憶するのか?

ある身体器官の感覚を、別の感覚言語へと翻訳すること――それは、半透明の身体に宿る記憶を「共感覚的に解剖 [19]」することにほかならない。虹彩に隠された微細な皺や、わずかなピクセルの色調は、もはや沈黙する表面ではない。それは耳による読み取りが可能な楽譜となり、私的なものは抽象化され、匿名の共鳴として絡み合ってゆく。音へと翻訳された虹彩は、もはや「誰かの眼」ではない。空気のなかに消えていくその音は、非人称的な物質性をあらわにし、個性と匿名性とが同時に共存する。回転する内なる宇宙は、一瞬外界へと呼び出されるが、やがて外部の宇宙へと再び消えてゆくに過ぎない。このテーブルの上に置かれた瞬間、AIの虹彩は再び翻訳され、音として立ち上がる。回転するたびに生まれる音と沈黙は、ログインしている自己と、やがてログアウトしていく運命とを同時に照らし出す。記憶の塵は、宇宙の空白を抱えた原点へと回帰し、問いの軌跡は絶えず風景として描出され続ける。

メディアとは、すなわち記憶である [20] 。

あるインドの修行者が、私の虹彩に刻まれた宇宙を読み取り、そっと囁いた [21]――「ここに、あなたの前世と人類全体の輪廻が重なっている」と。私の虹彩のなかには、古代洞窟壁画の残像と、今朝方見た切り抜き動画がコラージュされている。透明になった私の身体はもはや見つからず、「記憶の劇場」から消え去って久しい。遠く彼方では、ある稜線が青緑の夕映えを抱いてふたたび湧き上がり、その麓では、古い丘と湖が無数のデータ・クラスタのように揺らめいている。ヴァールブルクの巨大な記憶のボード [22] は、いまやアルゴリズムの手で新たに紡がれなおし、劇場のなかには観察者を持たない監視カメラ [23] が内包されている。宙に吊るされた天使オファニム [24] は、その回転する輪の周りに無数の眼をもち、光は金属的波長となる。霊とコードとピクセルとは、ひとつの呼吸として結ばれ、やがて八十八 の星座 [25] となった。舞台は暮れ、客席は沈黙している。しかし、車輪のなかの車輪は止まることなく回転し続け、私たちはその軌跡の一部として、何度でも再び始まる。瞳の外は、もうひとつの眼が開いている。巨大な虹彩の水晶膜は、ルネサンスが約束した救済の円形天蓋 [26] のように虚空に吊られ、そこから私のことを見つめ返す。記憶はもはや現象を伴わずに成長し、観客は速度の捕虜として試される。かつて記憶の貯蔵庫であった過去の叙事詩は、リアルタイムで更新される過剰なフィードの奔流のなかで、ただ忘却の時を待っている [27]。個人の痛みさえもコンテンツへと落とし込まれるこの高速の隙間のなかで、私は「呼吸」を取り出し、ゆるやかな筆跡を残す[28]。身振りによって曖昧に残された、低解像度の空白の境界は、私たちそれぞれのイメージとして上塗りされていくだけに過ぎない。新しいデジタル・アルゴリズムのアウラ[29] が「いま―――ここ[30]」の反復のなかで生成され、そして同じ台詞は「九度の転生[31]」を経て、声として完成する。

入力(人間)→AI生成(機械)→ 選択(人間)→プリンター(機械)→切り抜き(人間)→コラージュ貼付け(人間)→スキャン(機械)→アンプリンター(機械)→筆跡(人間)

無限の速度で駆け抜けていたものたちが、ついに静止の一点へと帰結し[32]、巨大な騒音は、ようやく静けさへと収束してゆく。この刹那は、数億光年の彼方の超新星の残光が瞳孔に染み入るように、ボードレールが脆弱さのうちに永遠を掴もうとしたあの瞬間 [33] にも似ている。そしてようやく、記憶の扇の奥に折りたたまれていた固有の記憶が、微細な炭酸の泡のように―――宇宙的な爆発とともに―――湧き上がるのだ。

「シャンぺン・スーパーノヴァ [34]」

*1――このテクストは、概念と感覚を構成し、置換し、重ね合わせる言語的構成の実験である。「記憶の劇場」「虹彩」「風景」「AI」「コラージュ」といったモチーフが、反復と変奏を繰り返しながら相互に再文脈化される。そしてテクスト自体がもつ、この緩やかな構造は、記憶の脆弱さを露わにすると同時に、意味の深度を掘り下げていく。イメージと言語が交錯する地点において、アビ・ヴァールブルク(Aby Warburg)の「ムネモシュネ・アトラス(Mnemosyne Atlas)」、ヴァルター・ベンヤミン(Walter Benjamin)の「星座(Konstellation)」、そしてジュリオ・カミッロ(Giulio Camillo)の「記憶の劇場(Theatre of Memory)」に見られるような図像学的思考が呼び起こされる。そこでは、テクストとイメージのあいだに、互いに記憶を呼び覚ますような構成が実験的に試みられる。同時にこれらすべての過程は、AI時代によって分断された感覚とデータとを結びつけ直して再構成する「構成的思考(configurational thinking)」の実践でもある。このテクストが中心的に扱う3つの方向性は以下のとおりである。第一に、「もはや自分の記憶を所有することはできない」という自覚を持つこと。デジタル時代において、記憶は純粋な個人的経験として収まることはなく、アルゴリズムと標準化の回路によって調整される。こうした集団的―機械的記憶へと移行している現状を、批判的にまなざす。第二に、「AIという虹彩」「サウンドに変換された眼」「共感覚的解剖」といった概念を通して、テクノロジーが感覚を再符号化し、記憶を解体する地点を探る。これはたんなるテクノロジー礼賛ではなく、知覚の脱人間化やアイデンティティの再調整に対する文化人類学的応答である。第三に、「風景が私を見ている」という転倒的な感覚のなかで、主体はもはや観察者ではなく、世界のうちに「置かれた存在」として位置づけられる。そのとき、監視と受動性のあいだで揺らぐ人間のさまが浮かび上がる。こうした理論に基づいた思考は、私の創作プロセスとも密接に結びついている。「九度の転生」と名づけた絵画制作のプロセス─入力、AI生成、選択、出力、切り抜き、コラージュ、スキャン、アンプリント、筆跡─は、人間と機械の間で繰り返される相互作用を通じて、イメージの層を蓄積していく「再帰的ジェスチャー(recursive gesture)」である。この過程のなかで立ち現れる「ゆるやかな筆跡」は、テクノロジーによる加速の時代において、感覚と時間性を取り戻そうとする美学的・倫理的応答である。それはポストデジタル絵画の延長線上において、絵画というメディウムが果たしうる存在論的抵抗であり、感覚的思考の更新であり、そしてAIによってもたらされたイメージ過剰の時代に対する、ひとつのクリエイティブな突破口でもある。

*2――筆者は《Half Water, Half Fish》(2007)の制作に際し、観客が置かれる状況について以下のように述べた。「観客それぞれの空間が明確な境界によって隔てられ、各々がまるで島であるかのように存在し、あたかもこの世界に誰もいないかのように互いのコミュニケーションを断つとき ─すなわち作用・反作用の行為を断ち切るとき─その境界は自らの身体を取り囲むひとつの舞台、ひとつの場となる。真の観客たちは戸惑いながらも、その個々の舞台のあいだに、ほとんど強制的に置かれてしまうのではないか。これこそが、境界の生起によってできる、不慣れな真空状態に陥る経験である。親しみのうちにあったものが、瞬時に不慣れな何かへと反転し、境界によって生まれたその空間の穴に、独り転がり落ちるという空間の奇妙な体験である」。 イ・ジンジュン『どこにでもあり、どこにもない(Nowhere in Somewhere: 어디에나 있는, 어디에도 없는)』(ソウル:マルンモ、2023年、26-33頁)。ブレヒト(Bertolt Brecht)もまた、観客と舞台を分断することで、舞台上の出来事が一種の現実であるかのような錯覚を生む「第四の壁」について論じ、「境界」という主題を扱っている。 ベルトルト・ブレヒト(Bertolt Brecht)『演劇論(Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic)』(ジョン・ウィレット﹇John Willett﹈訳、Eyre Methuen Ltd., 、1974年、136頁)。または次を参照。ジャック・ランシエール(Jacques Rancière)『解放された観客(The Emancipated Spectator)』(グレゴリー・エリオット﹇Gregory Elliott﹈訳、Verso、2011年)。

*3――「記憶の劇場」は、ジュリオ・カミッロ(Giulio Camillo、註7参照)が構想した「記憶の宮殿」(註6参照)における一体系である。この劇場は、七 段にせり上がる反円形の舞台で構成され、それぞれの段は7つの通路に分かれ、区画ごとに図像で飾られた扉がひとつずつ設けられている。唯一の「観客」は、舞台に立つのではなく、客席側から外を向き、7×7=49の扉に刻まれたイメージを見上げる構造となっている。 フランシス・アミーリア・イェイツ(Frances Amelia Yates)『記憶術(The Art of Memory)』(ArkPaperbacks)、1984年、129-159頁)。

*4――柄谷行人は、「風景」の発見とは、外部の環境への無関心のうちに「内的人間(inner man)」の内部で生じる過程で発生すると論じている。柄谷によると、風景とは外部(outside)を見ない者によってのみ知覚されるものである。 柄谷行人(Kōjin Karatani)『日本近代文学の起源(Origins of Modern Japanese Literature)』(ブレット・デ・バリー[Brett de Bary]訳、デューク大学出版局、1993年、25頁)。

*5――馬山自由貿易地域は、国家および地域経済の発展を目的として1970年に設立された、韓国初の外国人投資誘致および投資拠点である。「馬山自由貿易地域」、産業通商資源部 馬山自由貿易地域管理院、2025年8月13日アクセス。http://www.motie.go.kr/kftz/masan/freeTradeArea/aboutFreeTradeArea.do.

*6――古代ギリシアの叙情詩人ケオス島のシモーニデース(Simonides)は、記憶術の発明者として知られている。とある宴会場で屋根の崩落事故が起き、犠牲者の遺体が識別不能となった際、彼が参列者の座席位置を記憶していたことで、遺族は犠牲者の身元を確認することができた。 フランシス・アミーリア・イェイツ『記憶術』(1-2頁)。

*7――「記憶の宮殿(memory palace)」は、「場所法(method of loci)」とも呼ばれる記憶術である。これは、想像上の建物のなかにいくつかの場所を順序づけて思い描き、それぞれの場所に特定のイメージを結びつけて記憶する方法である。思い出したい内容をたどる際には、その仮想空間を心のなかで歩きながら、順に思い出していく仕組みになっている。フランシス・アミーリア・イェイツ『記憶術』(3頁)。

*8――ジュリオ・カミッロ(Giulio Camillo Delminio)はルネサンス期の博学者である。16世紀を代表するもっとも著名な思想家の一人で、「記憶の劇場」(註2参照)を構想した人物として知られている。 フランシス・アミーリア・イェイツ『記憶術』(129-159頁)。

*9――木材や石炭からタールを蒸留して得られるクレオソート(creosote)は、19世紀半ば以降、木材の防腐処理に広く用いられてきた。クレオソートが塗装された電信柱や鉄道の枕木から漂う独特の匂いは、一般的に「コールタール」という名で知られている。「クレオソート(Creosote)」、米国環境保護庁(US EPA)、2025年8月13日アクセス。 https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticideproducts/creosote.

*10――著者の故郷である馬山の尚南洞(サンナムドン)にある路地を指す。「行政区域」、昌原特例市、2025年8月13日アクセス。 https://www.changwon.go.kr/cwportal/10671/10672/10680.web.

*11――馬山自由貿易地域が設置されて以降、馬山は産業化すると同時に、廃棄物や重金属を含む産業廃水による海洋汚染が発生した。「馬山湾/公害現場告発(環境を守ろう)」『中央日報』1994年1月29日。https://www.joongang.co.kr/article/2851857

*12――龍馬(ヨンマ)山、齊飛(ジェビ)山、ムンディ山を総称して筆者が用いる言葉。なかでも「ムンディ山」は、かつてハンセン病患者たちが集住していたと伝えられる山の俗称である。「ムンドゥンイ(문둥이)」は歴史的にハンセン病患者を指す語であり、慶尚道の方言では「ムンディ(문디)」となる。現在ではこの語は特定の集団に対する蔑称とされている。筆者は、幼少期に急速な産業化によって自宅周辺の山々の自然が破壊され、赤茶けた禿山だけが残ったことを回想している。

*13――筆者が講演でしばしば用いる隠喩。筆者は、AIを人間の欲望と投影を照射する「行政規模の反射面」にたとえている。人工知能が人間のデータを蓄積し、人々がもっとも見たいものや聞きたいものをキュレーションすることで確証バイアスを強化し、ときにそれを増幅させる危険性について、作家はこれまで繰り返し懸念を表明してきた。

*14――「視聴覚的補綴(prosthesis)の産業的規模の拡散に加え、幼少期からのリアルタイム通信メディアへの恒常的接続によって、私たちは、ますます精緻化する心的イメージの符号化と、それに反比例するかのように持続的に低下する記憶の保持率や想起率を、日々目の当たりにしている。すなわち、私たちは、急速な「記憶の固定化(mnemonic consolidation)」が崩壊する只中にいるのである」。 〝With the industrial proliferation of visual and audiovisual p rostheses and unrest rained use of instantaneous-transmission equipment from earliest childhood onwards, we now routinely see the encoding of increasingly elaborate mental images together with a steady decline in retention rates and recall. In other words we are looking at the rapid collapse of mnemonic consolidation.〞 ポール・ヴィリリオ(Paul Virilio)『視覚機械(The Vision Machine)』(ジュリー・ローズ[Julie Rose]訳、インディアナ大学出版局、1994年、6-7頁)。[訳者註]註内の日本語による引用は、筆者による英語引用箇所の、訳者による英日翻訳である。

*15――ユク・ホイ(Yuk Hui)は、論考「機械とエコロジー(Machine and Ecology)」において、人工的な集合的記憶を介して進行するサイバネティックな総体化、及び人工知能の問題について論じている。 ユク・ホイ(Yuk Hui)「機械とエコロジー(Machine and Ecology)」『宇宙技芸(Cosmotechnics)』(ロンドン:Routledge、2021年、54-66頁)。併せて以下を参照。ビャオ・シアン(Biao Xiang)「グリッド・リアクション─COVID-19およびSARSにおける移動制限の比較(〝Grid Reaction: Comparing Mobility Restrictions during COVID-19 and SARS〞)」 『モーラボ・インベントリー(MoLab Inventory)』(マックス・プランク研究所、2021年)。https://www.eth.mpg.de/molab-inventory/securitizing-mobilities/grid-reaction-comparing-mobilityrestrictions-during-covid19-and-sars

*16――ベンヤミンは、「遊び(play)」と「記憶」の関係について論じている。幼年期の遊びは、記憶を形成する一つの形態である。またベンヤミンは、記憶そのものについて、「遊び」が展開する「劇場」であると捉えている。 ヴァルター・ベンヤミン(Walter Benjamin)『一九〇〇年ごろのベルリンの幼年時代(Berlin Childhood around 1900)』(ハワード・アイランド[Howard Eiland]訳、ハーバード大学出版局、2006年)。

*17――次の一節は、ベンヤミンによる言葉を筆者が翻訳したものである─〝What Proust began so playfully became awesomely serious. He who has once begun to open the fan of memory never comes to the end of its segments; no image satisfies him, for he has seen that it can be unfolded, and only in its folds does the truth reside.〞ヴァルター・ベンヤミン(Walter Benjamin)『一方通行路 他の著作(One-Way Street and Other Writings)』(エドマンド・ジェフコット[Edmund Jephcott]およびキングズリー・ショーター[Kingsley Shorter]訳、NLB、1979年、295-296頁)。

*18――2010年7月1日、昌原市・馬山市・鎮海市は統合され、新たに昌原市となった。作家の故郷である馬山は、かつて人口50万人規模にまで発 展した都市であったが、行政統合後、その名称は事実上その役目を終えたかのように、姿を消した。「昌原の歴史」『昌原特例市』2025年8月13日アクセス。 https://www.changwon.go.kr/cwportal/10671/10700/10702.web

*19――筆者は、人工知能が人間の感覚的経験を解釈し、相互にマッピングしながら再構成していくプロセスを、「共感覚的解剖(synaesthetic dissection)」という造語で説明している。共感覚とは、ある感覚刺激が通常は結びつかない別の感覚経験を引き起こす現象を指す。たとえば、味覚が 色の印象を呼び起こすといったものである。マイケル・J・バニッシー(Michael J. Banissy)ほか「共感覚─イントロダクション(Synesthesia: an introduction)」『フロンティアーズ・イン・サイコロジー(Frontiers in Psychology)』第5巻(2014年、1414頁)。 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01414

歴史的な類例としては、オランダの解剖学者・植物学者フレデリクス・ルイシ(Frederik Ruysch, 1638–1731)が挙げられる。彼は保存標本の収集や死後血管注入の精緻なテクニックを持っていたこと知られ、硫化水銀をベースにした注入液を用いて組織に赤みを出し、まるで生きているかのような質感を再現した。ルイシは自らの解剖標本を「ヴァニタス(vanitas)」風のタブローとして配置し、科学的精密さを、人間存在の有限性への象徴的省察に結びつけていた。ルーカス・ボール(Lucas Boer)「フレデリクス・ルイシ(1638–1731)─その奇形学的遺産の歴史的視点と現代的分析(Frederik Ruysch (1638–1731): Historical perspective and contemporary analysis of his teratological legacy)」『アメリカン・ジャーナル・オブ・メディカル・ジェネティクス パートA(American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A)』第173巻、第1号(2017年、16-41頁)。 https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.37663

歴史的な類例としては、オランダの解剖学者・植物学者フレデリクス・ルイシ(Frederik Ruysch, 1638–1731)が挙げられる。彼は保存標本の収集や死後血管注入の精緻なテクニックを持っていたこと知られ、硫化水銀をベースにした注入液を用いて組織に赤みを出し、まるで生きているかのような質感を再現した。ルイシは自らの解剖標本を「ヴァニタス(vanitas)」風のタブローとして配置し、科学的精密さを、人間存在の有限性への象徴的省察に結びつけていた。ルーカス・ボール(Lucas Boer)「フレデリクス・ルイシ(1638–1731)─その奇形学的遺産の歴史的視点と現代的分析(Frederik Ruysch (1638–1731): Historical perspective and contemporary analysis of his teratological legacy)」『アメリカン・ジャーナル・オブ・メディカル・ジェネティクス パートA(American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A)』第173巻、第1号(2017年、16-41頁)。 https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.37663

*20――「メディウムこそが記憶である(The medium is the memory.)」。ロザリンド・E・クラウス(Rosalind E. Krauss)『アンダー・ブルー・カップ(Under Blue Cup)』(マサチューセッツ工科大学出版局、2011年、3頁)。

*21――筆者が出会ったインドの行者は、虹彩を通して前世の記憶、および身体と心の傷を読み取った *22―――『ムネモシュネ・アトラス(Bilderatlas Mnemosyne)』は、ドイツの美術史家アビ・モリッツ・ヴァールブルク(Aby Moritz Warburg)の代表的な業績の一つである。未完のまま残されたこの作品は、多様なイメージが貼り付けられた黒いパネル群から構成されており、その枚数やイメージのキュレーションは、絶えず変化していた。 「Bilderatlas Mnemosyne」 『ウォーバーグ・インスティテュート(The Warburg Institute)』2025年8月12日アクセス。 https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/archive/bilderatlasmnemosyne

*23――現代美術家シュ・ビン(徐冰)は、2017年に映画『とんぼの目(Dragonfly Eyes)』を発表した。監視カメラの映像を編集し、中国で暮らす一人の女性の架空の物語を構築したこの作品は、視覚と意味、そして現実の断片と「現実」そのものとの関係を探究している。 「シュ・ビン《トンボの目》をMoMAが上映(MoMA Presents Xu Bing’s Dragonfly Eyes)」 『ニューヨーク近代美術館(Museum of Modern Art, MoMA)』(2025年8月13日アクセス)。https://www.moma.org/calendar/film/5009

「プロジェクト(project)」『シュ・ビン(Xu Bing)公式サイト(Official Website of Xu Bing)』(2025年8月13日アクセス)。 https://www. xubing.com/en/work/details/469?type=project

「プロジェクト(project)」『シュ・ビン(Xu Bing)公式サイト(Official Website of Xu Bing)』(2025年8月13日アクセス)。 https://www. xubing.com/en/work/details/469?type=project

*24――生成型人工知能の発展により、かつては想像や絵画のなかにしか存在しなかったイメージは、驚くほど生々しく可視化できるようになった。例えば、聖書に登場する、回転する車輪に眼がびっしりとついている存在―――オファニム(Ophanim)―――のイメージがAIによって生成されている。 『エゼキエル書』1:15–21、10:9–17〔改訂版聖書〕。インスタグラム上のある投稿では、AIが生成したオファニムの映像が紹介され、「聖書に忠実な天使(biblically accurate angels)」と評されている。 The AI Bible(@theaibibleofficial)「聖書に忠実な天使(Biblically Accurate Angels)」インスタグラム、2023年12月24日。 https://www.instagram.com/reel/C1NKOTEvn0j/?hl=en

*25――「星座(The Constellations)」 『国際天文学連合(International Astronomical Union)』2025年8月12日アクセス。 https: // iauarchive.eso.org/public/themes/constellations/

*26――フランチェスコ・ボッティチーニ(Francesco Botticini)による《聖母被昇天(The Assumption of the Virgin)》では、聖母マリアが死後、 雲と金色の光に包まれた天上へと昇り、キリストの祝福を受ける場面が描かれている。この場面では、天と地の統合を象徴する構図のなかで、円蓋状のドームが天空に開かれた場面が視覚化されている。

*27――「聖母被昇天(The Assumption of the Virgin)」『ナショナル・ギャラリー(The National Gallery)』2025年8月12日アクセス。 https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/francescobotticini-theassumption-of-the-virgin

*28――ポール・ヴィリリオ(Paul Virilio)は、自身の概念である「ドロモロジー(dromology=速度学)」を通じて、技術による速度の加速が社会に及 ぼす影響を論じている。 ポール・ヴィリリオ(Paul Virilio)『速度と政治(Speed and Politics)』(マーク・ポリゾッティ[Marc Polizzotti]訳、マサ チューセッツ工科大学出版局、2006年)。ヴィリリオは、「高度な技術によって加速した速度は、私たちを現象への直接的な知覚から遠ざけ、ついには意識そのものの消滅へと向かわせる」と語っている。〝The development of high technical speeds would thus result in the disappearance of consciousness as the direct perception of phenomena that inform us of our own existence.〞 ポール・ヴィリリオ(Paul Virilio)『消滅の美学(The Aesthetics of Disappearance)』(フィリップ・ベッチマン﹇Philip Beitchman﹈訳、Semiotext(e)、1991年、104頁)。[訳者註]註内の日本語による引用は、筆者による英語引用箇所の、訳者による英日翻訳である。

*29――こうしたイメージは、あらゆる場所に存在しながら、同時にどこにも存在しせずに循環している。これらは、純粋なデータ・パケットとして具現化された、ベンヤミン的な「現在時(Jetztzeit)」である。クリス・ベルデン=アダムズ(Kris Belden-Adams)「ベンヤミンとボードレールによるユビキタスで非物質的なポストデジタル写真の理論化(Theorizing the Ubiquitous, Immaterial, Post-digital Photograph via Benjamin and Baudelaire)」『再生産されるイメージとテクスト(Reproducing Images and Texts (la Reproduction des Images et des Textes))』(カースティ・ベル﹇Kirsty Bell﹈およびフィリップ・カーネル[Philippe Kaenel]編、ライデン:Brill、2021年、57-66頁)。 クリス・ベルデン=アダムズ(Kris Belden-Adams)「あらゆる場所と同時にどこにも―――ユビキタスで非物質的なポストデジタル写真の理論化(Everywhere and Nowhere, simultaneously: Theorizing the Ubiquitous, Immaterial, Post-Digital Photograph)」『モバイルとユビキタス・メディア―――批判的かつ国際的視座から(Mobile and Ubiquitous Media: Critical and International Perspectives)』(マイケル・S・ドーブス[Michael S. Daubs]およびヴィンセント・R・マンゼロール[Vincent R.Manzerolle]編、ニューヨーク:Peter Lang、2017年、163-179頁)。

*30――ベンヤミンは、自らのエッセイのなかで「現在時[Jetztzeit]」という概念について明示的に言及している。彼によれば、「歴史は構成の対象で あって、この構成の場を成すのは均質で空虚な時間ではなく、現在時(Jetztzeit)によって満たされた時間である」。〝History is the subject of a structure whose site is not homogenous, empty time, but time filled by the presence of the now. [Jetztzeit].〞 ヴァルター・ベンヤミン(Walter Benjamin)「歴史の概念について(Theses on the Philosophy of History [Über den Begriff der Geschichte])」 『クリティカル・セオリー・アンド・ソサエティ(Critical Theory and Society)』(スティーヴン・エリック・ブロナー[Stephen Eric Bronner]およびダグラス・マッケイ・ケルナー[Douglas MacKay Kellner]編、ロンドン: Routledge、2020年、255-263頁)。[訳者註]註内の日本語訳は、筆者による英語引用箇所に該当する、以下の既存の邦訳を参照した。「歴史の概念について」 『ベンヤミン・コレクション1 近代の意味』(浅井健 二郎編訳、ちくま学芸文庫、1995年、659頁)。「『現在時』は、歴史的唯物論が導火線を取り付ける「爆薬」として位置づけられている。その目的は、歴史を「充満したもの」、すなわち「現在的」で爆発的かつ転覆的な瞬間で満たされたものとして捉える時間概念によって、歴史の連続体を爆破することにある。」〝an explosive [Explosivstoff] to which historical materialism adds the fuse. The aim is to explode the continuum of history with the aid of a conception of historical time that perceives it as ‘full’, as charged with ‘present’, explosive, subversive moments.〞 ミカエル・ローウィ(Michael Löwy)『火災警報─ベンヤミン「歴史の概念について」を読む(Fire Alarm: Reading Walter Benjamin’s ‘On the Concept of History’)』(クリス・ターナー﹇Chris Turner﹈訳、ロンドン:Verso、2005年、 87-88頁)。[訳者註]註内の日本語による引用は、筆者による英語引用箇所の、訳者による英日翻訳である。

*31――「九度の転生」とは、筆者が2025年に発表したハイブリッド・ポストデジタル・コラージュ=ペインティング連作《On Some Faraway Shore》における、九段階の制作プロセスを指す。原画像は、データ・キュレーションとAI合成から始まり、印刷、手作業によるコラージュ、再デジタル化、再合成、キャンバスへの下絵印刷を経て、最終的な絵画的介入に至る。これらの過程は、デジタルと物質的メディウムのあいだを往還しながら絶えず変換を重ねる、循環的なジェスチャーとして構成されている。各段階で生み出された成果物は次の段階の入力値としてフィードバックされ、イメージは「再誕生」を繰り返す。

*32――アンリ・ベルクソン(Henri Bergson)の「まったく純粋な持続とは自我が生きることに身をまかせ、現在の状態とそれに先行する諸状態とのあいだに境界を設けることを差しひかえる場合に、意識の諸状態がとる形態である」。(〝Pure duration is the form which the succession of our conscious states assumes when our ego lets itself live, when it refrains from separating its present state from its former states.〞) アンリ・ベルクソン(Henri Bergson)『時間と自由(Time and Free Will: Essai sur les données immédiates de la conscience)』(F・L・ポグソン[F. L. Pogson]訳、マイノラ:ドーヴァー出版[Dover Publications]、2001年、100頁)。﹇訳者註﹈註内の日本語訳は、筆者による英語引用箇所に該当する、以下の既存の邦訳を参照した。「等質的時間と具体的持続」『時間と自由』(アンリ・ベルクソン著、平井啓之訳、白水社、1990年、100頁)。ベルクソンがこの「流れ」を創造性へとつながるものとして示唆したのに対し、ポール・ヴィリリオ(Paul Virilio)は、技術的速度の極点がこの過程を反転させ、停滞と創発の停止をもたらすと論じた。 アンリ・ベルクソン(Henri Bergson)『創造的進化(Creative Evolution: L’évolution créatrice)』(アーサー・ミッチェル﹇Arthur Mitchell﹈訳、ニューヨーク:Holt and Company、1911年)。ポール・ヴィリリオ(Paul Virilio)『消滅の美学(The Aesthetics of Disappearance)』(フィリップ・ベッチマン[Philip Beitchman]訳、ニューヨーク: Semiotext(e)、1991年)。

*33――シャルル・ボードレール(Charles Baudelaire)「近代生活の画家(Le Peintre de la vie moderne)」『モダン・アートとモダニズム(Modern Art and Modernism)』(ロンドン:Routledge、2018年、23-28頁)。

*34――「Champagne Supernova」オアシス(Oasis)によるアルバム《(What’s the Story) Morning Glory?》(Creation Records, 1995)の 第5曲。

[参考文献]

The AI Bible. 〝Biblically Accurate Angels.〞 Instagram, December 24, 2023. [The AI Bible(@theaibibleofficial)「聖書に忠実な天使」インスタグラム、2023年12月24日] https://www.instagram.com/reel/C1NKOTEvn0j/?hl=en Banissy, Michael J., et al. 〝Synesthesia: An Introduction.〞 Frontiers in Psychology 5(2014): 1414.

[マイケル・J・バニッシーほか「共感覚―――イントロダクション」『フロンティアーズ・イン・サイコロジー』第5巻(2014年)] https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01414

Baudelaire, Charles. 〝The Painter of Modern Life.〞 In Modern Art and Modernism. London: Routledge, 2018.

[シャルル・ボードレール「近代生活の画家」『モダン・アートとモダニズム』(ロンドン:Routledge、2018年)]

Belden-Adams, Kris. 〝Everywhere and Nowhere, Simultaneously: Theorizing the Ubiquitous, Immaterial, Post-Digital Photograph.〞 In Mobile and Ubiquitous Media: Critical and International Perspectives, edited by Michael S. Daubs and Vincent R.Manzerolle, 163–179. New York: Peter Lang, 2017.

[クリス・ベルデン=アダムズ「あらゆる場所と同時にどこにも│ユビキタスで非物質的なポストデジタル写真の理論化」『モバイルとユビキタス・メディア│批判的かつ国際的視座から』(マイケル・S・ドーブス、ヴィンセ ント・R・マンゼロール編、ニューヨーク:Peter Lang、2017年)]

Belden-Adams, Kris. 〝Theorizing the Ubiquitous, Immaterial, Post-Digital Photograph via Benjamin and Baudelaire.〞 In Reproducing Images and Texts, edited by Kirsty Bell and Philippe Kaenel, 57–66. Leiden: Brill, 2021.

[クリス・ベルデン=アダムズ「ベンヤミンとボードレールによるユビキタスで非物質的なポストデジタル写真の理論化」『再生産されるイメージとテクスト』(カースティ・ベル、フィリップ・カーネル編、ライデン:Brill、2021年)]Benjamin, Walter. Berlin Childhood around 1900. Translated by Howard Eiland. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

[ヴァルター・ベンヤミン『一九〇〇年ごろのベルリンの幼年時代』(ハワード・アイランド訳、ハーバード大学出版局、2006年)] Benjamin, Walter. One-Way Street and Other Writings. Translated by Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter. London: NLB, 1979.

[ヴァルター・ベンヤミン『一方通行路 他の著作』(エドマンド・ジェフコット、キングズリー・ショーター訳、NLB、1979年)]

Benjamin, Walter. 〝Theses on the Philosophy of History.〞 In Critical Theory and Society, edited by Stephen Eric Bronner and Douglas MacKay Kellner, 255–263. London: Routledge, 2020. [ヴァルター・ベンヤミン「歴史の概念について」『クリティカル・セオリー・アンド・ソサエティ』(スティーヴン・E・ブロナー、ダグラス・M・ケルナー編、ロンドン:Routledge、2020年)]

[マイケル・J・バニッシーほか「共感覚―――イントロダクション」『フロンティアーズ・イン・サイコロジー』第5巻(2014年)] https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01414

Baudelaire, Charles. 〝The Painter of Modern Life.〞 In Modern Art and Modernism. London: Routledge, 2018.

[シャルル・ボードレール「近代生活の画家」『モダン・アートとモダニズム』(ロンドン:Routledge、2018年)]

Belden-Adams, Kris. 〝Everywhere and Nowhere, Simultaneously: Theorizing the Ubiquitous, Immaterial, Post-Digital Photograph.〞 In Mobile and Ubiquitous Media: Critical and International Perspectives, edited by Michael S. Daubs and Vincent R.Manzerolle, 163–179. New York: Peter Lang, 2017.

[クリス・ベルデン=アダムズ「あらゆる場所と同時にどこにも│ユビキタスで非物質的なポストデジタル写真の理論化」『モバイルとユビキタス・メディア│批判的かつ国際的視座から』(マイケル・S・ドーブス、ヴィンセ ント・R・マンゼロール編、ニューヨーク:Peter Lang、2017年)]

Belden-Adams, Kris. 〝Theorizing the Ubiquitous, Immaterial, Post-Digital Photograph via Benjamin and Baudelaire.〞 In Reproducing Images and Texts, edited by Kirsty Bell and Philippe Kaenel, 57–66. Leiden: Brill, 2021.

[クリス・ベルデン=アダムズ「ベンヤミンとボードレールによるユビキタスで非物質的なポストデジタル写真の理論化」『再生産されるイメージとテクスト』(カースティ・ベル、フィリップ・カーネル編、ライデン:Brill、2021年)]Benjamin, Walter. Berlin Childhood around 1900. Translated by Howard Eiland. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

[ヴァルター・ベンヤミン『一九〇〇年ごろのベルリンの幼年時代』(ハワード・アイランド訳、ハーバード大学出版局、2006年)] Benjamin, Walter. One-Way Street and Other Writings. Translated by Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter. London: NLB, 1979.

[ヴァルター・ベンヤミン『一方通行路 他の著作』(エドマンド・ジェフコット、キングズリー・ショーター訳、NLB、1979年)]

Benjamin, Walter. 〝Theses on the Philosophy of History.〞 In Critical Theory and Society, edited by Stephen Eric Bronner and Douglas MacKay Kellner, 255–263. London: Routledge, 2020. [ヴァルター・ベンヤミン「歴史の概念について」『クリティカル・セオリー・アンド・ソサエティ』(スティーヴン・E・ブロナー、ダグラス・M・ケルナー編、ロンドン:Routledge、2020年)]

Bergson, Henri. Creative Evolution. Translated by Arthur Mitchell. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1911. [アンリ・ベルクソン『創造的進化』(アーサー・ミッチェル訳、ニューヨーク:Holt and Company、1911年)] Bergson, Henri. Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness. Translated by F. L. Pogson. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2001. [アンリ・ベルクソン『時間と自由』(F・L・ポグソン訳、ドーヴァー出版、2001年)] Brecht, Bertolt. Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic. Edited and translated by John Willett. London: Eyre Methuen, 1974. [ベルトルト・ブレヒト『演劇論』(ジョン・ウィレット訳、Eyre Methuen、 1974年)]

Karatani, Kōjin. Origins of Modern Japanese Literature. Translated by Brett de Bary. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993. [柄谷行人『日本近代文学の起源』(ブレット・デ・バリー訳、デューク大学出版局、1993年)] Krauss, Rosalind E. Under Blue Cup. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011. [ロザリンド・E・クラウス『アンダー・ブルー・カップ』(MIT Press、2011年)] Löwy, Michael. Fire Alarm: Reading Walter Benjamin’s 〝On the Concept of History.〞 Translated by Chris Turner. London: Verso, 2005.

[ミカエル・ローウィ『火災警報─ベンヤミン「歴史の概念について」を読む』(クリス・ターナー訳、ロンドン:Verso、2005年)]

Rancière, Jacques. The Emancipated Spectator. Translated by Gregory Elliott. London: Verso, 2011. [ジャック・ランシエール『解放された観客』(グレゴリー・エリオット訳、Verso、2011年)]

Virilio, Paul. The Aesthetics of Disappearance. Translated by Philip Beitchman. New York: Semiotext(e), 1991. [ポール・ヴィリリオ『消滅の美学』(フィリップ・ベッチマン訳、Semiotext(e)、1991年)]

Virilio, Paul. Speed and Politics. Translated by Marc Polizzotti. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006. [ポール・ヴィリリオ『速度と政治』(マーク・ポリゾッティ訳、MIT Press、2006年)] Virilio, Paul. The Vision Machine. Translated by Julie Rose. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994. [ポール・ヴィリリオ『視覚機械』(ジュリー・ローズ訳、インディアナ大学出版局、1994年)] Warburg Institute. 〝Bilderatlas Mnemosyne.〞 Accessed August 12, 2025. [「Bilderatlas Mnemosyne」『ウォーバーグ・インスティテュート』 2025年8月12日アクセス]

https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/archive/bilderatlas-mnemosyne

Karatani, Kōjin. Origins of Modern Japanese Literature. Translated by Brett de Bary. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993. [柄谷行人『日本近代文学の起源』(ブレット・デ・バリー訳、デューク大学出版局、1993年)] Krauss, Rosalind E. Under Blue Cup. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011. [ロザリンド・E・クラウス『アンダー・ブルー・カップ』(MIT Press、2011年)] Löwy, Michael. Fire Alarm: Reading Walter Benjamin’s 〝On the Concept of History.〞 Translated by Chris Turner. London: Verso, 2005.

[ミカエル・ローウィ『火災警報─ベンヤミン「歴史の概念について」を読む』(クリス・ターナー訳、ロンドン:Verso、2005年)]

Rancière, Jacques. The Emancipated Spectator. Translated by Gregory Elliott. London: Verso, 2011. [ジャック・ランシエール『解放された観客』(グレゴリー・エリオット訳、Verso、2011年)]

Virilio, Paul. The Aesthetics of Disappearance. Translated by Philip Beitchman. New York: Semiotext(e), 1991. [ポール・ヴィリリオ『消滅の美学』(フィリップ・ベッチマン訳、Semiotext(e)、1991年)]

Virilio, Paul. Speed and Politics. Translated by Marc Polizzotti. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006. [ポール・ヴィリリオ『速度と政治』(マーク・ポリゾッティ訳、MIT Press、2006年)] Virilio, Paul. The Vision Machine. Translated by Julie Rose. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994. [ポール・ヴィリリオ『視覚機械』(ジュリー・ローズ訳、インディアナ大学出版局、1994年)] Warburg Institute. 〝Bilderatlas Mnemosyne.〞 Accessed August 12, 2025. [「Bilderatlas Mnemosyne」『ウォーバーグ・インスティテュート』 2025年8月12日アクセス]

https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/archive/bilderatlas-mnemosyne

Yates, Frances A. The Art of Memory. London: Ark Paperbacks, 1984. [フランシス・A・イェイツ『記憶術』(Ark Paperbacks、1984年)]

Yuk Hui. 〝Machine and Ecology.〞 In Cosmotechnics, 54–66. London: Routledge, 2021. [ユク・ホイ「機械とエコロジー」『現代思想』2024年7月号「ウィーナーとサイバネティクスの未来」特集(原島大輔訳)参照] [引用について] 本文中に引用した文献のうち、既存の日本語訳があるものは以下を参照した。 *17 「ベルリン年代記」『ベンヤミン・コレクション6 断片の力』(浅井健二郎編訳、ちくま学芸文庫、2012年、445頁)。 *30 「歴史の概念について」 『ベンヤミン・コレクション1 近代の意味』(浅井健二郎編訳、ちくま学芸文庫、1995年、659頁)。 *32 「等質的時間と具体的持続」 『時間と自由』(アンリ・ベルクソン著、平井啓之訳、白水社、1990年、100頁)。

Yuk Hui. 〝Machine and Ecology.〞 In Cosmotechnics, 54–66. London: Routledge, 2021. [ユク・ホイ「機械とエコロジー」『現代思想』2024年7月号「ウィーナーとサイバネティクスの未来」特集(原島大輔訳)参照] [引用について] 本文中に引用した文献のうち、既存の日本語訳があるものは以下を参照した。 *17 「ベルリン年代記」『ベンヤミン・コレクション6 断片の力』(浅井健二郎編訳、ちくま学芸文庫、2012年、445頁)。 *30 「歴史の概念について」 『ベンヤミン・コレクション1 近代の意味』(浅井健二郎編訳、ちくま学芸文庫、1995年、659頁)。 *32 「等質的時間と具体的持続」 『時間と自由』(アンリ・ベルクソン著、平井啓之訳、白水社、1990年、100頁)。